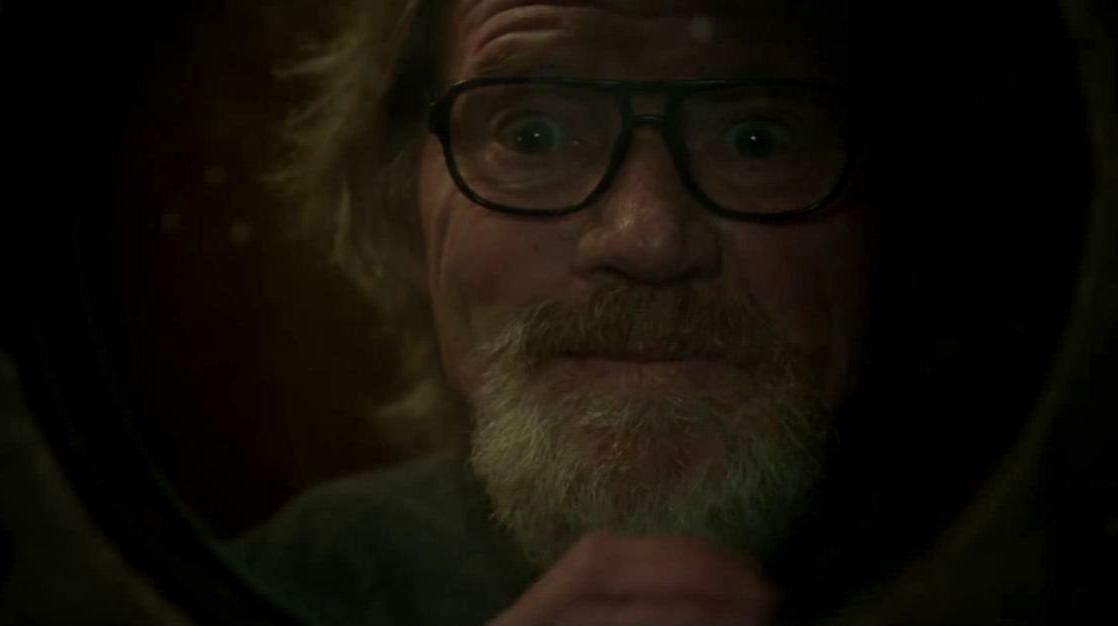

I’ve not seen a John Woo film in nearly 25 years. This is the legendary director who made Face/Off, The Killer, Hard Boiled, Hard Target, Bullet in the Head, and A Better Tomorrow. All of them cult shoot ‘em ups with a legion of fans. He’s made a bunch of movies since, but none of them were made in Hollywood. With Silent Night, starring Joel Kinnaman, with support from US rapper Kid Cudi, it’s being billed as John Woo’s Stateside comeback, which is a little tenuous, as the movie was shot in Mexico with a Mexican crew.

Kinnaman plays ordinary man Brian Godlock. He’s married to Saya (Catalina Sandino Moreno). They live in a rough suburban neighbourhood. They had a young boy who died on Christmas Eve as a result of being hit by a stray bullet when two warring gangs came hooning down their street firing machine guns at each other. In a desperate rage Godlock took chase only to have the kingpin, Playa (Harold Torres), shoot and maim him. With one of the bullets lodged in this throat, Godlock’s voice is stolen from him.

The entire movie uses this “plot device” as a narrative stylistic: there is no dialogue spoken in the movie whatsoever. That’s fine, as Robert Archer Lynn’s wholly unremarkable screenplay is a bare bones narrative anyway.

Godlock recovers from his wounds and goes into deep vengeance mode; body-building, weapons-training, precision-driving, and perfecting his steely-eyed expression. Poor Saya, she is left on the sidelines, and soon enough exists stage left. Seems Godlock is more concerned with exacting his revenge than nurturing and rebuilding his family life with the mother of his son who is hurting just as much.

Crime must pay. But it’s the audience that will suffer.

In the early 90s this movie would’ve starred Eric Roberts as the vengeful father, Annabella Sciorra as his mournful wife, and John Leguizamo as the Latin American gangster. I’d have watched that. But for this we get Joel Kinnaman. I’m not a fan of Kinnaman’s acting (he was one of the worst things about the recent Altered Carbon adaptation), so I tolerated him not having to deliver lines. Moreno is solid as his wife, but she has an entirely thankless role, as does Cudi as a tardy detective.

With more producers in the Silent Night stew than you can throw a stick at, a couple of them from the John Wick movies, you can feel the hard-boiled vibe they’re trying for, but the stylistic gusto that made Woo the action maestro that other wannabe action directors looked up to is virtually non-existent here. This is choreographed and shot like a video game, with cartoonish violence that has no emotional impact and characters you feel little to no empathy for.

The John Wick movies upped the combat game with hugely elaborate - albeit incredibly far-fetched - fight sequences. The last couple of Rambo movies upped the graphic violence game to an extreme, almost absurd level. Ben Wheatley’s Free Fire and Alex Garland’s Dredd employed characters who were genuinely interesting, whilst delivering the carnage with style and panache. These are all far superior modern action movies to what John Woo has just made.

A curious, yet wasted opportunity is Playa’s young smack victim girlfriend, played by Valeria Santaella, who we anticipate may have some kind of relevance in the movie’s final act, only to show, rather pathetically, that in her drug-addled state she’s actually a better shot than any of Playa’s gun-toting cronies. Go figure.

My real beef with Silent Night concerns two key action movie elements. The first is the heavy use of CGI over practical effects. I know it’s cheaper to do the bullet wounds with CGI, rather than use squibs on set, but man, the practical effects make Woo’s early films so much more impressive. The one apparent use of practical special effects makeup is the scene where surgeons remove the bullet from Godlock’s throat. An unnecessarily explicit, lingering scene.

The second element, and this is most strange, is the movie’s sound design. From what I can tell the sound for the entire film was added in post. That’s not entirely unusual, Italian productions have been doing it for decades, what is odd is how impactful action moments on screen in Silent Night has no corresponding sound effect, and much of the action, especially during combat, sounds like it’s coming from another room, the audio pushed way back in the mix. This was apparent early in the movie and it continues through the entire film, almost as if there is an audio track missing from the final mix. If this was a deliberate design, it’s a weird artistic decision, as it is most distracting. Seriously, the sound mix in Silent Night is stripped and weird, and not in a good way.

Silent Night is a hollow experience. Vacuous and inane it clings desperately to a tacky sentimentality. A Hallmark card splattered with blood. In an attempt to woo back his Western fans the once great director has shot himself in the foot.