US/France | 2001 | Directed by David Lynch

Logline: Following a car accident an amnesiac seeks the aid of a young Hollywood-hopeful as they search for clues and answers in a twisting, nightmarish quest for truth.

An accident is a terrible event …

Part One: She found herself the perfect mystery.

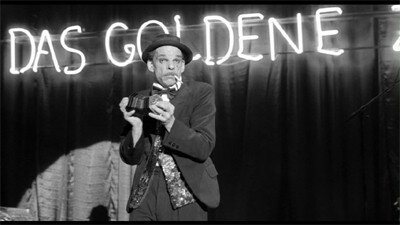

Blonde Betty Elms arrives in sunny Los Angeles, with rose-tinted eyes, and Irene and her companion wish her the very best of luck in making it in Hollywood, Betty is sure to be a bright burning star, but the mysterious raven who calls herself Rita crosses her path, suffering from amnesia, anxious about the huge amount of money in her purse, and Betty wants to help, excited by the discovery of adventure and allure; she’s falling for this voluptuous siren, all ebony eyes and knowing smiles, but Coco, the landlady is suspicious, because strange Louise Bonner said someone was in trouble, something bad is going to happen, and at Betty’s audition the director remarks “very good, really, I mean it was forced maybe, but still humanistic, yeah, very good, really, really,” and Betty feels much better, and whispers to Rita “I’m in love with you”, and Rita replies “Go with me somewhere,” into the night, the cabaret Silencio, where all is recorded, it is all an illusion, leaving Betty to shudder; her nightmare seizure shattering her sweet dream, while Rebekah Del Rio croons “Crying” in Spanish, and the blue key fits the hole in the blue box from the black purse; Betty is engulfed in the in-between, and Rita is overwhelmed by the darkness …

Part Two: A sad illusion.

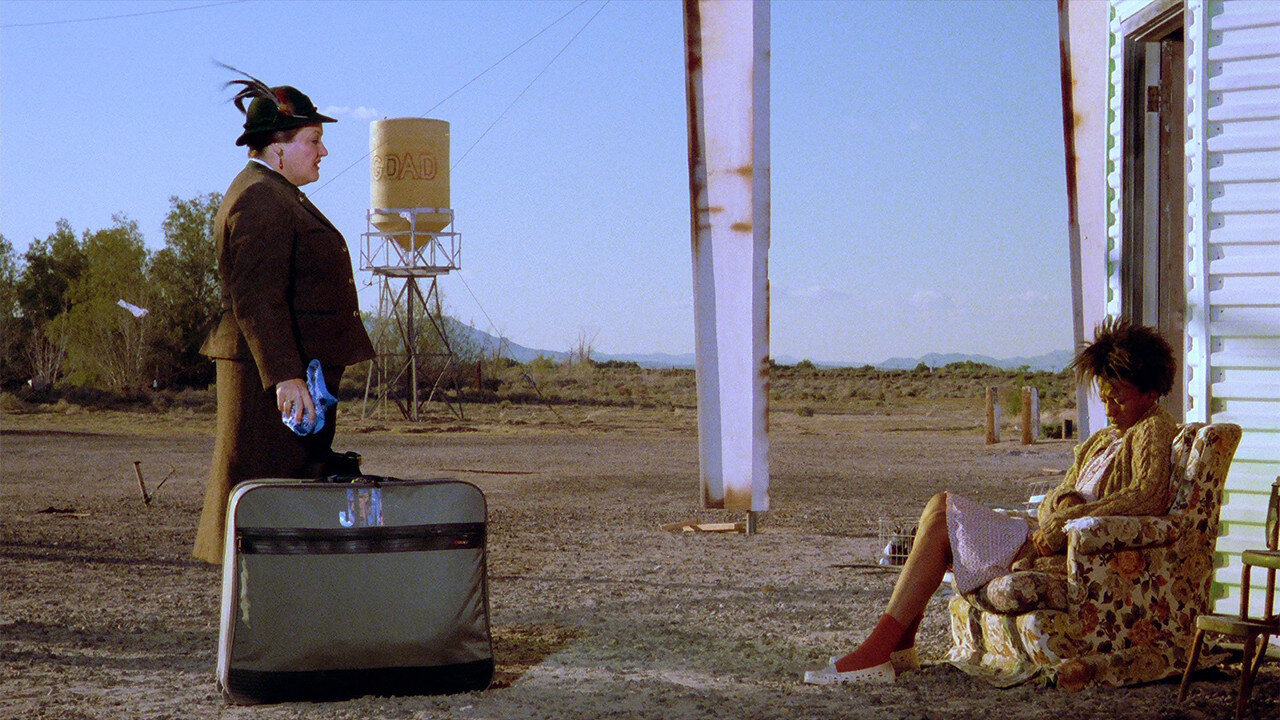

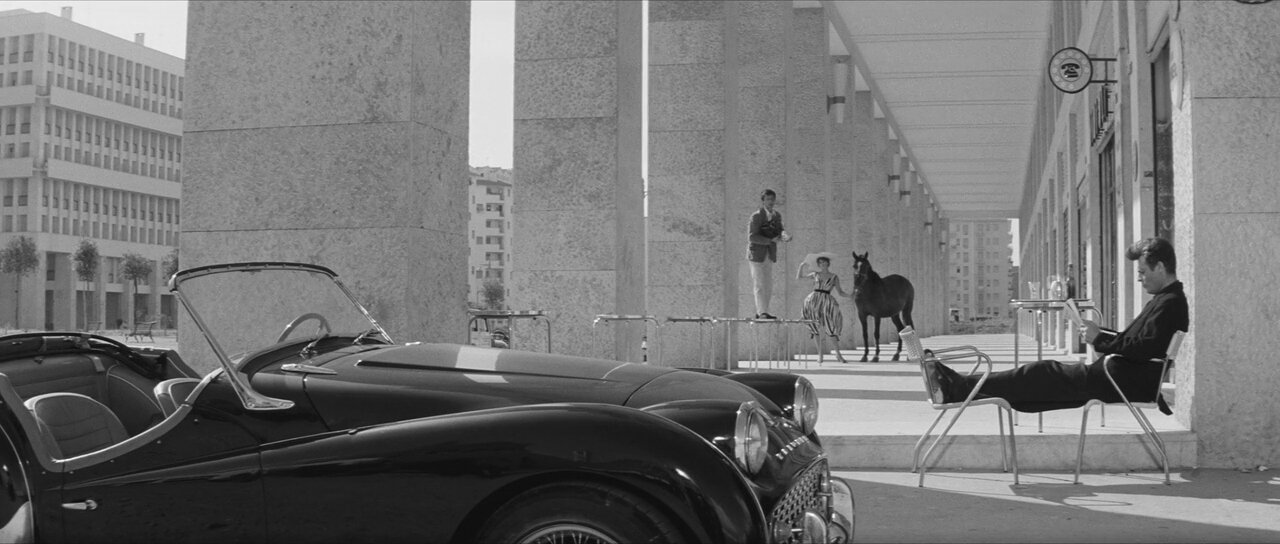

Hot shot director Adam Kesher is having problems, because Sylvia North’s story is no longer his movie, everything will be shut down unless he casts Carmilla Rhodes, even though it’s not a recommendation; “This is the girl,” but he’s had enough of interference, so he heads into the Hollywood Hills to his pad, but wife Lorraine is screwing the pool guy, while his assistant informs him a cowboy wants to rendezvous at Beechwood Canyon corral, where a man’s attitude does some ways, the way his life will be, and the brow-less man informs Adam that “You will see me one more time if you do good, you will see me two more times if you do bad,” but it doesn’t matter anymore because the Stetson man has told the pretty girl, “Time to wake up,” to the body on the bed, the corpse in the bedroom, “Camilla, you’ve come back!” cries Diane, a shell of her former self, rubbing one out furiously, desperately, on the sofa, the casting couch, “Hello it’s me, leave a message,” at 1612 Havenhurst, or is that 6980 Mulholland Dr., “What are you doing, we don’t stop here,” it’s a short cut, “Well, here’s to love” …

Part Three: Love.

Doin’ the Jitterbug baby, led keen Diane Selwyn to the bright lights big city of dreams, where everything is not what it seems, where the half-night shadowed through the undergrowth, the glimmer of neon from the City of Angels beckoned, and Tinseltown glittered, but not all of it is gold; the scarlet blush of infatuation, the crimson rage of jealousy, the blood-red lampshade, the grand piano ashtray, the dirty white shower robe, the velvet purple gown, the glare of the studio redheads and blondes blaring down, blinding the ingénue, she crossed the line, hired the clumsy killer who gave her the key, a desperate girl whose innocent dreams were shattered by the betrayal of a lover’s stab in the heart of her American Dream …

A flashback borne from an enigma disguised as a riddle masquerading as a puzzle pretending to be a chimera that reveals itself to be a pitch-black mockery reflected off the jagged fragments of the American Nightmare. David Lynch’s masterful fabrication of indulgent machinations, arch plot devices and cryptic filmic symbolism, weaves the elusive narrative strands of the dramatic thriller into a convoluted and delicious mind-fuck.

Mulholland Drive is the desolate boulevard within his trilogy of psychogenic fugues - Lost Highway (1997) was the treacherous off-ramp and Inland Empire (2007) was the tenebrous avenue - swerving along that famous long and winding road that caresses the hilltops of Hollywood, cutting through the elaborate figments of the Lynchian imagination, and curling back on itself like a marvellously dangerous and slippery Möbius strip.

Naomi Watts gives a career performance as Betty/Diane, Laura Elena Harring is fatally seductive as Rita/Carmilla, Justin Theroux is arrogantly cool as Adam, while a motley crew – a rogue’s gallery, if you will – of peripheral actors (Ann Miller, Lee Grant, Dan Hedaya, Robert Forster, James Karen, Marcus Graham, Lori Heuring, Billy Ray Cyrus, Missy Crider, Melissa George, Monty “Lafayette” Montgomery, Mark Pellegrino, and Michael J. Anderson as Mr. Roque) play the rooks and pawns of this strategically unfolding ciné-oneirodynia.

Angelo Badalamenti provides the proverbial musical broodiness (and makes a rare on-screen cameo as an espresso-swilling movie exec). Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger provide a rather putrid corpse. Long-time collaborators Mary Sweeney is Lynch’s partner-in-narrative-structural-crime (a.k.a. his editor and later, very briefly his wife) and Jack Fisk is on design duties.

When the blue-haired lady in the balcony seats of the night club whispers “Silencio”, the dream fabric has been torn asunder, the fantasy bubble has burst; the suicidal tears before bedtime have been spilled like the blood on the pillow. Humiliation was the game that burned like the flames of betrayal. It’s dog eat dog and the creatures climbing to stardom are savage beasts who smile like assassins as they lead you down the sickly-sweet-scented garden path. A box office hit mirrors the gangster’s mark, and the audition that works is one that feels hard, but you keep it real even though the truths hurt. Reality is a lie, it’s the fiction that counts, or at least it’s the illusion that lingers longest in the movie projected in the sad lover’s mind … on the dark subconscious corners of Mulholland Dr.

And the bittersweet smell of freshly-brewed coffee hangs in the air like a curious memory.