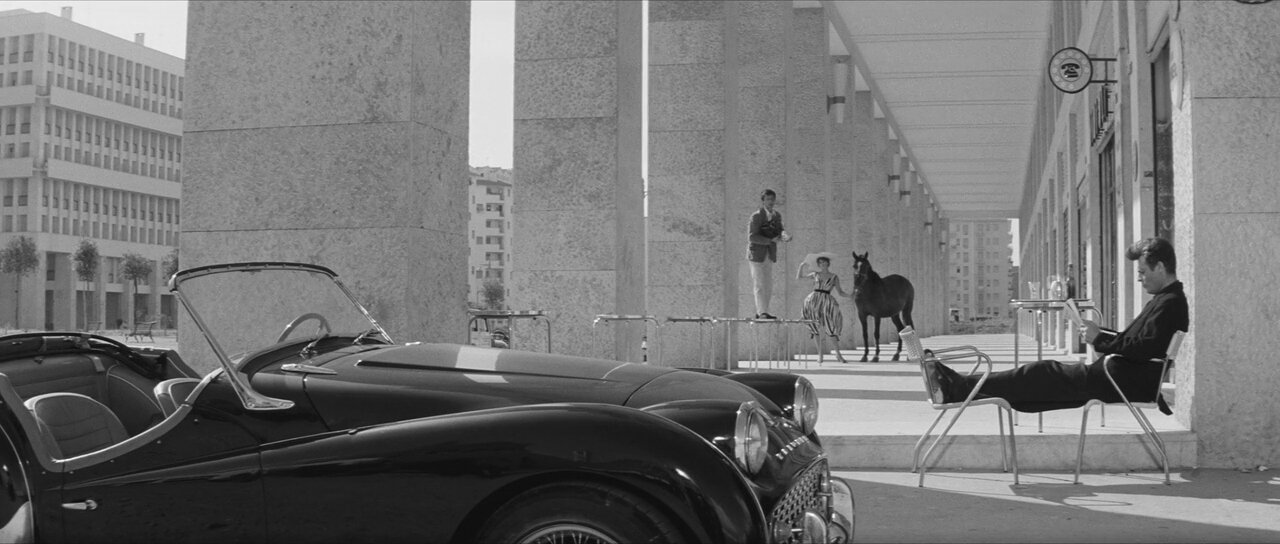

Italy | 1960 | Directed by Federico Fellini

Logline: A listless playboy journalist drifts in and around Rome over the course of several days and nights following celebrities and dealing with the breakdown of his marriage.

While not the masterstroke of cinema 8½ is, La Dolce Vita, which translates as The Sweet Life, is a bittersweet portrait of sensual ennui and the pursuit of happiness, an ironic spin on the cult of celebrity, the passion for attention, the importance of being in between. This is Fellini’s ode to the jaded affluence of existence, the existentialism of narcissism. Or perhaps it’s simply a love affair with the city of Rome.

Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni) is the film’s centerpiece. He is in virtually every scene of the three-hour movie. There is virtually no plot, only a series of vignettes, observations on relationships and the mechanics of social interaction, laced with cynicism, both subjective and objective. The corruption of the adulthood juxtaposed against the purity of youth, glimpsed, but never grasped. La Dolce Vita is a curious creature.

The most striking element of La Dolce Vita is not the subject matter, but the aesthetics. It is a superb-looking movie, from the opening images of a large Christ statue being transported via helicopter across the skyline of Rome to the final image of Marcello being led away along a beach having failed to understand what young Paola (Valeria Ciangottini) was gesticulating from across the inlet (she was asking him about his novel which was indicated by her pretending to type). It is Paola’s innocent charm that has eluded Marcello, and the irony is that her personality is what Marcello craves, yet he can’t see the forest for the trees.

Surrounding him are the elaborate fabrications, the false machinations, the fibs and lies, the disguises and the garden paths, that contribute to the big picture that is Marcello’s world of conceit. He is strung along by the aloof charm of Maddalena (Anouk Aimee), he is briefly infatuated with the voluptuous allure of American movie star Sylvia (Anita Ekberg), he is hounded and howled at by his insecure wife Emma (Yvonne Furneaux), and he is haunted by the jaded perspective of life and family of friend Steiner (Alain Cuny).

There are dozens and dozens of other peripheral characters, some with substantial speaking parts, and countless others as featured extras (watch for a young Nico), in fact there are over one hundred roles that are listed as uncredited on IMDb. Receiving due recognition within a Fellini movie is a rare thing, c’est la vie.

Fellini’s pre-occupation with the role of male identity, his relationship with the female kind, and an underlying sense of misanthropy is prevalent through many of his films, but none so acutely as in La Dolce Vita. The character of Paparazzo (Walter Santesso), the keen-as-mustard celebrity photographer, has resulted in a household word: paparazzi (the plural term). The word translates roughly as “sparrow” (in one Italian dialect, whilst in another it means “annoying fly”). Fellini felt the photographers that scurry around celebrities reminded him of hopping sparrows. Of course, they can also be interpreted as annoying flies.

La Dolce Vita is exhausting, but there are more than enough moments within its meandering narrative pseudo-arc that make it such an intriguing excursion. As I mentioned, it’s about aesthetics, and Fellini has such elegant and glamorous taste in design and form, from architecture to cars, from sculpture to women, at the risk of siding with his objectification, it’s hard to resist his immaculate eye.