Cult Projections: An authentic Maltese-Australian supernatural story! That has to be a first! What is your own Maltese heritage, and is this the first time you’ve written something specifically with your heritage as the cultural backdrop to the story?

Ryan: One of the few instances of Maltese-Australian scripted drama - period! Both my parents are Maltese, having immigrated here as children in the 1960s. Dad’s first home was actually in Greystanes, NSW! Back then, it was a real hotspot for the Maltese community in Australia. In addition to a healthy diet of classic horror movies from the local video store, Mum brought me up on a smörgåsbord of fairy tales, folktales and legends from all over the world. But apart from a couple of ghost stories, very few we read actually came from Malta. It wasn’t until Stephen Mifsud published his book The Maltese Bestiary in 2014, that I was exposed to a whole nightmare’s gallery of monsters and creatures lurking beneath Malta’s sunny exterior! I immediately saw the horror film potential in these and set about creating an “Original Maltese-Australian Horror Story” - a first for me as both writer and filmmaker.

CP: How did you approach the writing of Greystanes? Did you write the entire narrative as a single treatment and then broke it up into tiny bite-sized episodes, or did you write the episodes individually?

R: When I put the pitch together for Screen Australia, I mapped out what happened in each and every episode, cliffhangers and all! This became the roadmap for co-writer Matt Ferro and me, with each of the episodes having their own individual scripts.

CP: You’re no stranger to short form vertical format filmmaking, and with TikTok creatives on the rise and vertical format filmmaking a key part of TikTok’s content, was Greystanes designed specifically with TikTok in mind?

R: Greystanes was tailored specifically for Screen Australia and TikTok’s “Every Voice” initiative, which provides production funding for scripted or documentary series by creators from underrepresented backgrounds. With so little representation of the Maltese identity on Australian screens, how could I possibly resist this opportunity?! I was already on Screen Australia’s radar, having just been a finalist in their “Got A Minute” initiative - my entry for which (Tales From The Dark Web: Moira Hill) securing me an AACTA Award nomination for Best Digital Short Video in 2022.

CP: Superstition plays a large part of Greystanes’ plot. How significant was superstition in your own childhood, or even adulthood?

R: I am not superstitious, but I have family who are! In fact, one of the main plot points in Greystanes is based on the story of a curse on my mother’s side of the family. But to go into detail here, would spoil one of the twists in the series!

CP: The main character of young Samantha is “hooked on horror movies” as her older brother teases her, and she playfully videos herself making horror trailers - at her family’s expense. I can’t help but wonder if Samantha is based a little bit on yourself?

R: Damn right! And she is named after my father, Sam. Samantha is played by Chloe Delle-Vedove. Theatre geeks might recognise her as Young Anna or Jane Banks in Disney’s Sydney productions of Frozen and Mary Poppins, respectively. She was an absolute dream to work with and definitely one to watch!

CP: Tell us about Il-Ħaddiela, the sleep-demon. How did you come up with her appearance?

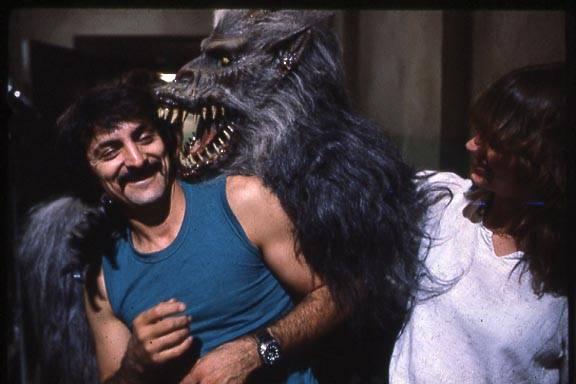

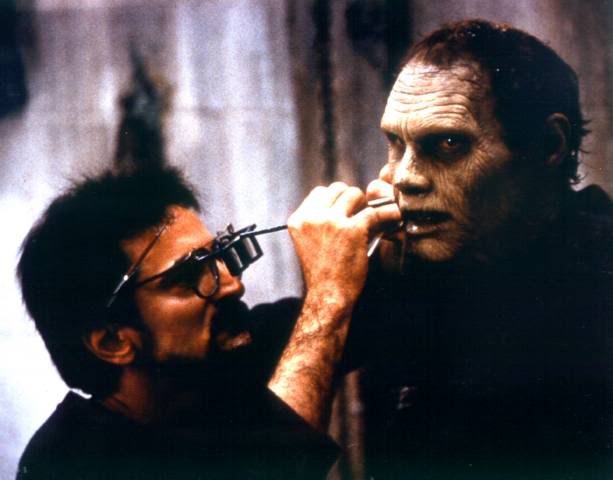

R: Every culture has its own version of the night hag or sleep-paralysis demon. In Malta we have Il-Ħaddiela - “the nightmare” - a female entity with four fingers, and no thumbs, on each hand. Designing a creature on a low-budget is a nightmare for any filmmaker, but fortunately Lewis P Morley (one of the masterminds behind the killer boar in Razorback) was up to the challenge. I drew inspiration from two sources: the horse’s head in Fuseli’s 1781 painting “The Nightmare” and some creepy photographs by William Mortensen, showcasing the voodoo masks he made for Tod Browning’s West of Zanzibar (1928). It was Lewis’ idea to dress her in Old Victorian Lace - which gave her a fantastically Gothic appearance, and coincidentally, reminded me of the doilies in my Nanna’s house!! There’s another character that pops up in the latter half of the series. I won’t give too much away but my brief to the creature designer was “Give me a store mannequin as if it were shat out by David Lynch”!

CP: Greystanes is filled with Maltese idioms and language, such as the names for grandparents and great-grandparents (Nanna and Nannu, Buz-Nannu and Buz-Nanna), the National dish (Pastizzi), what are some of the other Maltese references you’ve included?

R: The series opens at the annual Festa tal-Vitojra, a Maltese national holiday which celebrates the birth of Mary, Queen of Peace. We also have Gulepp tal-Harrub (Carob syrup) and Balbuljata (Maltese Scrambled Eggs with Tomatoes) - both play important roles in the narrative. On Greystanes I was very blessed to collaborate with AACTA-nominated Maltese actress Frances Duca (Ali’s Wedding), who plays Nanna. She was our unofficial Maltese consultant on set - even contributing some of the dialogue! - which made for a more authentic Maltese experience!

CP: Night of the Living Dead makes a brief appearance on TV, when Samantha is trying to watch it. Handy that the movie is now in the public domain! What are some of the horror and dark fantasy movies of your youth that you hold dear? Were there any specific ones that influenced Greystanes?

R: And one of the movies in her mountain of (public domain) VHS tapes is Paul Wegener’s The Golem (1920) - a nod to my 2020 short Golem. I grew up on a LOT of youth-centric horror and dark fantasy films. A lot of them shaped me as a creative and influenced Greystanes. Some of these include Poltergeist (1982), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983), Gremlins (1984), Return to Oz (1985) and The Witches (1990). I was also big on Universal’s Classic Monsters and Jim Henson’s darker work (like The Storyteller!) - both of which started my whole love affair with myths and monsters. One contemporary filmmaker that really inspires me is Guillermo del Toro. I’ve loved everything of his from Cronos to The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth to Pinocchio. No one handles the beauty - and horror - of monsters and fairy tales like him!

CP: There is a playful sense of humour lingering in the background of Greystanes, that pokes its head up every now and again, such as Samantha arming the water rifle with her Nanna’s yucky carob to fight Il-Ħaddiela with. Was the sly comedic element always part of the story?

R: Always. I’m really glad you picked up on that. When your protagonist is an eleven-year-old girl, it can’t all be doom and gloom! I took a lot of inspiration from the dark humour in Roald Dahl’s books for children like The BFG and The Witches, as well as my own observations of the Maltese culture from growing up with my grandparents. There were quite a few more jokes, but sadly, these were excised from the script or picture edit, due to pacing and/or tone.

CP: You’ve involved animation in some of your past short films, and there is some terrific silhouette work in Greystanes. How did you achieve that particular stylistic, especially the shot of the ocean liner in the distance with the waves in the foreground?

R: The silhouette work in Greystanes - what I call the “shadowplay” - was inspired by silhouette animation pioneer Lotte Reiniger, as well as bits I had seen from Jean Boullet’s lost animated adaptation of Dracula from 1962. I also wanted some of that grimy atmosphere we associate with Pre-Code Hollywood movies.

The sequence was boarded, then those storyboards were brought into Adobe Photoshop, where the final designs for the compositions and characters were worked out. These were then sent to After Effects, and married with stock elements such as waves, mist and moving clouds, which were given their own stylised treatments in the software. Everything you see in this sequence is the product of years of experimenting with compositing and layering on other projects. Things I learnt before the arrival of A.I.

CP: The special effects are excellent, in particular Il-Ħaddiela pushing through the ceiling a la Freddy Krueger in A Nightmare on Elm Street, and the fingers bursting through poor young Samantha’s chin! How did you achieve these impressive effects?

R: It’s funny, everyone says A Nightmare on Elm Street, but co-writer/producer Matt Ferro and I were thinking Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983)! That was one of the few instances of CGI in the series. Matt took a 3D scan of the Il-Ħaddiela mask wth his iPad and sent it over to his buddies, Joel and Elliot Goodman. They are the masterminds behind this effect! As for the fingers bursting through Sam’s chin, we constructed a large faux head of Sam from latex, and filmed it with one of my nieces’ fingers emerging through a crack in the “chin”. In the extreme close-ups, it’s the dummy, but on wider shots, we composited my niece’s fingers and the faux chin onto the real-life Sam. It’s proven to be one of the most memorable moments for our TikTok audience! Waking up to comments such as “Ewww, gross!” and “WTF?!” just puts a smile on my face.

CP: How much of Greystanes was made in the editing stages? Did you shoot a lot of coverage? What did you shoot on? What was it like working the kids, teens, and babies?

R: A lot of Greystanes was made in the edit and was a real test of my editorial skills! It was filmed by DOP Matt Ryan on the Sony FX6. Some days we had the A7SIII as a B-camera. Principal Photography was an intense, five-day shoot - budget and resources were tight, kids could only work a set number of hours, not a lot of time for extra coverage or even experimentation. After I did the rough cut, I took it upon myself to get behind an A7SIII and shoot a lot of second unit (mostly cutaways) and practical VFX to supplement what was already in the can. After a few months, I was able to beat it all into submission, with score, sound and colour - masterfully provided by Me-Lee Hay, Nick Keate and Lachlan Early, respectively - being the delicious cherries on top! Apart from the restrictions on set, the kids were amazing to work with… My (then) one-year-old niece, Georgia (who plays Sam’s baby cousin, Rianna), not so much! The poor thing was teething and was having none of my shit!

CP: What’s next?

R: Hopefully more horror and dark fantasy with that distinct Maltese voice! But with Greystanes only halfway through its 18-episode run and plans of re-engaging with audiences during Halloween, it could be a while before I start writing again!