UK/Australia/France | 2019 | Directed by Josephine Mackerras

Logline: When a married mother discovers her husband’s ruinous addiction to prostitutes she is forced into grappling with her own identity and self-determination.

Alice (Emilie Piponnier) is happily married with a caring career husband, François (Martin Swabey) and a young son Jules. They live in a Parisian apartment. One morning François says goodbye and vanishes for several days on end. Alice is confounded. Suddenly she is alone with a young child, with credit cards that have been cancelled, and heavy mortgage payments that are threatening to foreclose. Alice is desperate.

She soon discovers that her husband had been living a duplicitous life, addicted to high end prostitutes, and spending all his money, including all the savings Alice’s father had provided to help secure the apartment. Alice is devastated. But she holds it together. Just. The threat of destitution propels her into digging deeper into her husband’s sordid secret doings. As a result she attends the escort service’s screening and befriends Lisa (Chloé Boreham) who gives her a crash course in tailored sex work.

Soon enough the initially nervous Alice is earning good money, and has garnered a sense of independence. Her fragility has been conquered, and with it she has embraced a new lease on life. Then François suddenly re-appears, all pathetic and desperate for reconciliation, and her inner strength is challenged.

This is Aussie director Mackerras’ debut feature, having made several shorts. Although there is nothing Australian about the production, there are universal truths that lie at the heart of this extraordinary character study, penned by Mackerras. It’s easily the most remarkable relationship drama I’ve seen in a long time. It is small, and intimate, yet never once feels constrained or limited in its scope and execution.

An absolutely brilliant performance from Piponnier who totally owns the movie. But superb work from Boreham, who provides a wonderful sassiness, and perfect contrast to Alice’s rigidity and earnestness. Swabey is also very good, and it’s a difficult role to play. It’s easy to see that Mackerras has a true talent for directing actors. But her mise-en-scene is strong also, as is the score and cinematography. Alice is the kind of narrative that could easily have felt like a play being filmed, but never once suffers from that kind of staged unreality. In fact, there is a real sense of docu-drama to the film.

But Alice isn’t all grim fare, it possesses a lovely natural sense of humour, without the comedy feeling forced. Also - and this isn’t really apparent until the very end - Alice harbours a desire for freedom that she isn’t really aware of until she experiences a degree of it with her new friend Lisa. It’s the kind of freedom one can only experience physically, not just psychologically or spiritually. It becomes a kind of thematic, emotional core.

Alice is a truly wonderful film. An amazing example of a taut screenplay that doesn’t feel over-written, perfectly cast and given excellent direction, with production values that fit like hand in glove. Easily in my top three films of the year, make sure you see it.

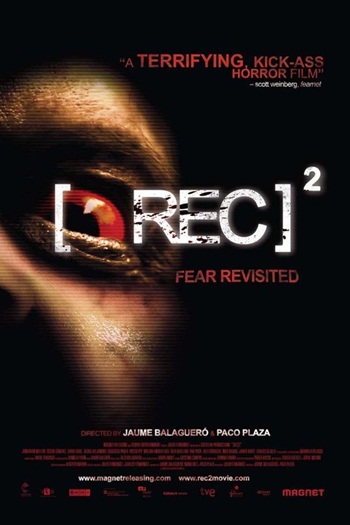

![[REC 2] Parte 3 HD.mp48.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/50d144f6e4b05aff8e5b9c8c/1539732263485-HR3D2FOLAF7U0IOMUU2H/%5BREC+2%5D+Parte+3+HD.mp48.jpg)