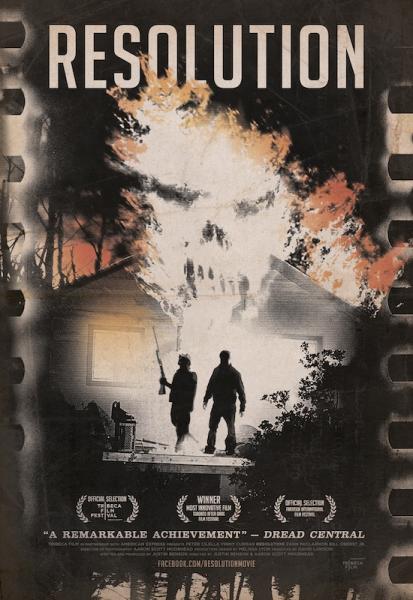

Cult Projections: For me Resolution was the standout movie from this year’s A Night Of Horror Film Festival in Sydney.

Justin: Oh cool! Thank you, very very much. That’s amazing. It was really unfortunate that that was one of the only festivals we didn’t manage to get to go to that we really wanted to go to; y’know, costs of getting to Australia, and all that. That means a lot to us though, so thank you!

CP: What’s your background together, and how did you share the directorial duties?

Justin: We met as interns at a commercial production company in Los Angeles; it was my last day and Aaron’s first day. It was this really unique situation where people could express to each other, “I wanna be a writer/director” and “I wanna be a director/DP”. And it was one of those weird things that happen where two people actually go do those things. And so we were working together more and more, on short films and music videos, and stuff like that. We had some money saved up to shoot a feature, and between the two of us we had so many do-it-yourself-filmmaking skills that we’d worked on over the years that we could actually go make our own feature for very little money.

CP: Although Resolution deals with the supernatural, there’s a science fiction element – a cosmic intrigue, if you will. Are you a both big science-fiction fans? Do you have favourite science-fiction horror movies?

Aaron: We absolutely love fantastic cinema. We have a rule, not a rule, but one of things that Justin and I bond on; we don’t just love sci-fi movies, or horror movies, we just love movies that are good. And we gravitate toward the strange, and that’s usually fantastic film and genre film. There are definitely favourite movies, like I love Children of Men. I love Children of Men. But I also love Jurassic Park.

CP: Now without wanting to pigeonhole you, how aware were you that you were contributing to the “found footage” sub-genre, but delivering something altogether leftfield, and decidedly original? Where did the screenplay come from?

Justin: The conception of the screenplay was several things. In the most general sense it was a desire to write a movie that is conceptually frightening, not just a jump-scare every fifteen minutes, not make it effects every fifteen minutes, but something that can really get under your skin. Something that Aaron and I found to be a conceptually frightening idea. There was x-amount of money in the cheque account: how do we create an effective movie where we’re not going to go beyond our means? Figuratively our movie is like a little kid wearing his dad’s clothes. A person who tries to make a Spielberg homage for ten thousand dollars; it’s like, oh man, that’s not good.

[all laugh]

Justin: Just trying to tell an actual scary story and give that experience in the theatre. For example, sometimes you get the question: what made you do a genre-bending movie that had comedy and drama? We never actually thought about it, but if you want to actually frighten people, if you want people to actually feel fear, and give them that experience while watching a movie, then you create realistic characters and you give levity to situations, and understated humour, and you give them conflicts in their lives, that maybe you don’t typically see in cinema. And the other thing is the Jaws thing, y’know? In Jaws there’s a monster in the water, and that’s awesome, really cool. But the monster in the water isn’t that effective without those really interesting men on the boat.

CP: Yeah, indeed. [pause] The screenplay is emotionally and psychologically complex, but what I also like is that it arrives at a very stark and resonant nightmare ending. Can you describe the importance to you both - as writer and co-directors – in delivering all, some, or none of the answers to the questions that you raise?

Justin: What is interesting about our movie is, well, we definitely know our movie is mysterious, but the reality is – upon second viewing or third viewing – people find there is a literal answer to every single question in the movie, I mean quite literally. Perhaps not what happens to them after the credits roll, but everything else, you watch it and absorb it, but it is there, very much there. There are wildly different interpretations to our movie, but there is also one definite interpretation. When people are watching it they’re like, “Oh, there’s a lot of David Lynch extractions here,” but maybe they’re just stylistic touches, visual poetry, whatever, but then the second or third time, they’re like, “Oh fuck, it’s all very literal.” It can be interpreted very directly if you want it to. We’ve heard the Lynch comparison on occasion, which is awesome because he’s, like, amazing, but his are open to interpretation. Ours can be open to interpretation, we don’t mind it, but there’s also one definite answer that’s buried in the subtext. But there are potential red herrings throughout the movie.

CP: We love red herrings. [pause] The relationship between Michael and Chris produces some wonderfully black comic dialogue, how important is humour in a horror movie that’s not a comedy, and how best should humour be integrated?

Justin: If you’re making a horror movie to scare people, let’s leave the genre side out of it, you have to really get them to identify with the characters, like the characters, and view these characters as real people, and the thing is, in real life people can make light of really dramatic situations, that’s realistic. If you’re trying to scare people you need to make realistic characters, have that levity, make jokes of situations, and all these things. It’s a necessary part of every type of movie, but especially if you want to do something that’s actually frightening.

CP: I quite agree. Frequently directors seem to fail in that. But you guys did a great job with the writing and casting.

Justin: Our actors delivered this to us on a silver platter. The script is pretty much exactly what you see on screen. But those guys are really, really talented guys. They just got it. 90% of good directing is good casting. And in that regard we directed very well.

[all laugh]

CP: Horror is probably more trendy amongst up and coming directors than it’s ever been. Is there a Golden Rule that all horror writers and/or directors should try to follow, and if so, what would that be?

Justin: You shouldn’t rely on make-up effects exclusively and you should try and do visual effects really cheaply, even if it looks bad. And if there’s no jump scare every ten pages you’ve failed. No, we’re kidding, we’re kidding! There are bad rules that a lot of people seem to follow. The good rule is - it’s not a rule in fact, but we wish it was – please be original. And we don’t mean, “Now you see my monster is wearing a mask, but also has a tail!” or “My zombies aren’t fast or slow, they’re medium zombies!” All that’s doing is putting a Band-Aid on the problem. We really feel there’s so much room for innovation. Not like what kind of monster, or what kind of genre you’re doing, but storytelling in general is in a really bad place, in that homage movies are becoming the norm. Even in indie film, where you don’t have to do it to get your money back. The Golden Rule is don’t do the thing that someone else just did. There’s no reason to do it. There’s NO reason to do that. Unless you’re just a businessman. When Aaron and I are working on material if someone else has done it, then we’re, like, well we can’t do it. That’s just how we work.

CP: Well congratulations, because that’s how I felt coming out of your movie at the festival; that finally some writer/directors delivering a horror movie that was fresh and original. [pause] Do you believe in the spirit world? UFOs? Do you believe in parallel universes?

Aaron: I’m not going to speak for Justin, although we don’t usually disagree on something. I personally do not believe in the spirit world. I think there are some rules of physics that we haven’t yet understood, there could be some really new stuff just around the corner, but in terms of the paranormal – at least the commonly accepted sub-culture version of it – I don’t think that exists.

CP: It’s always interesting when filmmakers are tackling this, as to whether they are coming from pure conviction or pure speculation.

Aaron: By the way, we love talking about it though, and not in the cynical way. We think it’s fascinating, fascinating.

CP: That’s like me; fascinated, but sceptical.

Justin: There’s an interesting thing in storytelling that one can do. There are a lot of places where supernatural phenomenon can fall apart logically. It all does eventually pretty much, but there are certain things, where it’s harder to deconstruct and make them fall apart for an audience, and those are fun to play with. If you can keep your audience distracted enough with some good jokes and some good drama you can kind of get them to believe in that and really get under their skin. But it’s tricky. There are supernatural phenomenon that you can Wikipedia and find the source of it, when in history that happened, and there’s stuff that you can’t. There’s stuff that requires a lot of thinking about. Kind of like the first ten minutes of The Exorcist, which for me makes that movie quite frightening. We’re not talking about a demon that’s from a religion I can Wikipedia and see that that religion derives from this religion. But with The Exorcist this thing is ancient and mysterious. It pre-dates history! It doesn’t follow arbitrary rules. And that’s what’s so frightening about that. There’s a halfway scientific biologist approach to a lot of the stuff we do, in that does it prey on our primal fears or on institutional fears. We’re more interested in the primal fears; scary on a conceptual level, rather than scary on an educational level.

CP: Are there any directors whose work you look to for inspiration? Any current directors that are exciting you at the moment?

Aaron: We’re inspired just by good work, like Ben Wheatley. Are you a Ben Wheatley fan?

CP: Yes, I love Kill List and Sightseers, and looking forward to A Field in England.

Aaron: A Field in England was shot for 250, 000 and he’s a fucking rock star. I love that, it’s so cool. We love the Soskia twins who did American Mary. On a bigger level, Cuaron for Gravity and Children of Men, obviously. We have big budget tastes; we both love Gore Verbinski. I grew up with Spielberg, although I’ll probably never make a movie like his. And we like Danny Boyle, we like his spirit quite a bit. And we like Richard Linklater.

CP: What next for you? Another collaboration?

Justin: Of course. Our next movie will be called Spring. It’s about a young man who leaves from California, with a lot of personal problems, and takes a nowhere trip to Italy, and sparks a romance with a girl on the southern coast of Italy. And we really feel these two are falling in love, but when they go their separate ways, we see her go through some transformations and we think is she a vampire, is she a werewolf, or is she some kind of Lovecraftian sea creature? But they all turn out to be red herrings, and what she turns out to be is, probably something that we shouldn’t put any kind of journalistic meaning to just yet. But it’s a new monster mythology of our own creation, and people who’ve read the script are like, “Oh I really like it because it reminds me of Cronenberg body horror, a very realistic character relationship thing.”

CP: Sounds very exciting.

Justin: It is. It’s the most exciting thing since A Field in England, my mom said.

CP: It’s been fabulous chatting with you guys. But your voices are very, very similar.

Justin: Yeah, we’re told that. Just pick arbitrarily. Would it be better if one of us, next time, attempted an Australian accent?

CP: If your attempt at an Australian accent is as bad as Tarantino’s then no.

Justin: I promise it’s worse.

[all laugh]

Justin: Oh, one last thing. Wake in Fright changed our lives.

CP: That’s actually my favourite Australian movie. That movie is fucking awesome.

Aaron: God, that movie is amazing. Absolutely incredible. I was horrified. I stopped drinking beer for two hours after I saw that movie. Two hours!!

CP: I know. It’s the true definition of the word: fug.

[all laugh]

CP: Hopefully with your next movie you can come out to the festival!

J/A: Thanks very much, great talking with you.