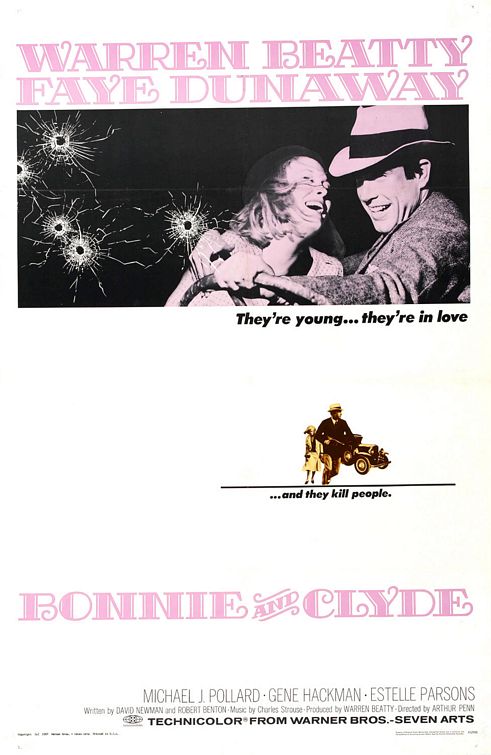

US | 1967 | Directed by Arthur Penn

Logline: A bored woman is seduced by a charming ex-con and, along with his brother and wife, and a simple-minded young man, they embark on a violent crime spree.

Here's the story of Bonnie and Clyde. / Now Bonnie and Clyde are the Barrow gang / I'm sure you all have read / How they rob and steal / And those who squeal / Are usually found dyin' or dead…

On the surface it's the perfect Hollywood crime tale; the inseparable couple with gorgeous looks and charm enough for six… shooter, that is. Robbing banks and stealing cars, eating whatever they like, sleeping wherever they like, smoking cigars and playing the fool, and shooting anyone who gets in their way. The true ballad of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow took place from 1930, until their brutal demise, under a hail of police bullets on a lonely stretch of Louisiana country road, May 23rd, 1934.

Warren Beatty acquired the rights and bought the script by David Newman and Robert Benton. A number of directors were offered the chance but declined, and eventually Beatty convinced Penn who brought a progressive melding of American and French New Wave style to the production. Although its hard now to imagine anyone else but Faye Dunaway as Bonnie, the role was offered to numerous other Hollywood stars first, including Jane Fonda, Tuesday Weld, Ann-Margret, Leslie Caron (Beatty’s then girlfriend), and Sue Lyon (who had played Lolita five years earlier).

Beatty and Dunaway are superb. Gene Hackman does a great job as Clyde’s brother Buck, who, along with his wife Blanche, played by Estelle Parsons (the real-life Blanche was considered better looking than Bonnie), and C.W. Moss (a scene-stealing Michael J. Pollard), were along for the violent ride, almost to the very end. Apparently the real-life Buck was shot through the temple, during a siege, but survived for several more days!

Penn’s direction is a engaging mix of light-hearted drama, verging on comedy, especially the chase scenes, which were obviously influenced by the Keystone cops of Hollywood’s yesteryear, and snatches of poignant romantic drama, most notably the intimate scenes between Bonnie and Clyde, which are also loaded with a sexual charge. Clyde’s impotency vs. Bonnie’s sexual yearning provides their relationship with a fabulous tension, and even extends as a metaphorical juxtaposition of the couple’s aggressive behaviour to others, and their confident, arrogant posturing.

Though the movie is not so remarkable for its episodic structure, it is the brazen thematic content, and the stylistic interweaving of drama and comedy in what was essentially an anti-authoritative piece, an apparent glorification of murderers, that was unlike anything seen by mainstream audiences up to that point. The release of the movie coincided with the breakdown of the Hays Code of movie censorship, and heralded what was later dubbed as the “New Hollywood”. Yes, the floodgates were opened, and the tide turned red.

Indeed the way violence was depicted on screen changed with Bonnie and Clyde, which was the first movie to show the firing of a gun and the direct impact on a victim within the same shot or frame. But not only that, there were several examples of a victim being shot in the face, which had never been seen before, and to add further realism, Penn had blood squibs employed on the actors, most notably in the movie’s famous end scene where Bonnie and Clyde are ambushed by police fire and, in stylised slow motion, peppered with bullets, Clyde rolling in dust-laden death throes beside the car, Bonnie’s lead-filled body slumping out of the bullet-ridden car door.

Poetic justice never looked so morbidly beautiful.

The movie is fifty this year, and, yet, watching it recently on the big screen in a lovely 2K restoration, very little has dated, even if it is a period movie. I’m a little surprised the movie hasn’t been given a contemporary re-boot, but then I’m reminded of Quentin Tarantino’s Natural Born Killers, and realised that’s exactly what he was doing, in his own extremist, ultra-stylised way, right down to the curious relationship between the gangsters and the public’s perception of them through the media.

Some day, they'll go down together / They'll bury them side by side / To a few, it'll be grief / To the law, a relief / But it's death for Bonnie and Clyde.