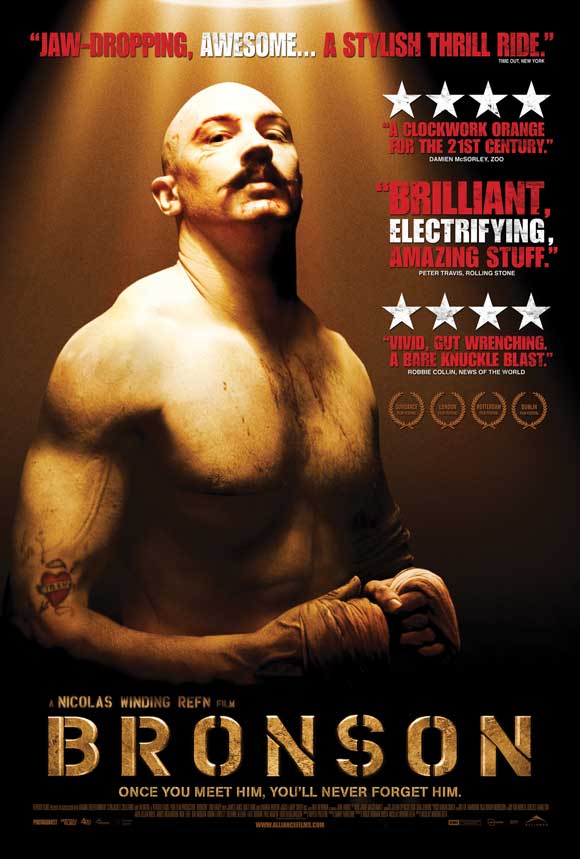

UK | 2009 | Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn

Logline: The prison life story of Michael Peterson, Britain’s most notorious criminal, who spent thirty years in solitary confinement.

The true story of one of the most violent, unruly, and headstrong prisoners of the British penal system who systematically sabotaged his own future, and yet made a name for himself via his alter-ego, Charlie Bronson, the prison raconteur extraordinaire, the cuckoo that flew over the clockwork orange, Bronson is a docu-drama-biopic unlike anything you've seen before.

A tour-de-force of narrative delivered in unconventional stylistics and driven by a central performance that seethes and blisters with a powerhouse charisma and volatile intent; Tom Hardy is Michael Peterson, who in 1974 was charged with the armed robbery of a post office and slapped with a seven-year sentence in one of England’s harsher gaols. Seven years stretched out to thirty-four, and Peterson adapted to life inside by licking the dish of bittersweet vengeance.

Authorities realised it was costing too much of the Queen’s resources to keep Peterson locked up as he repeatedly damaged prison property and injured prison security, not to mention the grievous bodily harm to himself and subsequent time in the prison infirmary. While he was briefly on the outside he hooked up with an illegal fight club, earned the nickname Charlie Bronson (after the gruff vigilante Hollywood actor), became romantically involved with a young woman (who subsequently duped him), but eventually landed himself back in the insular, oppressive realm he knew best.

Refn’s sound and vision is brilliantly executed, at times surreal, at times frighteningly realistic. Early 80s electro, synth-pop, and opera music adds distinct flavour, and the production design is very authentic. Presented like a pantomime flashback told as if Peterson, aka Bronson, is delivering a one-man stage show, his self-assurance dominates everything, as does his aggressive stranglehold on his destiny. Violence is his natural form of communication. He’s not dumb, but he’s no smart cookie either. He’s scuttled his options and seems resigned to the consequences of his actions.

What elevates this seemingly grim and savage portrait is the black sense of humour that permeates the entire movie. It’s dark and grotesque, coal black, boys from the blackstuff material. It leers and jeers and slaps and tickles in equal measures. One scene in particular will push a few scatological buttons! Apparently the real Michael Peterson is quite proud of the movie, especially excited about his legacy continuing on after his death, his toil and trouble immortalised on celluloid. British authorities were apparently none too impressed with Refn's liberal portrait.

The movie is filled with great supporting performances; too many to mention here, but suffice to say Refn’s natural talents in casting serves him well. Like his brilliant Pusher trilogy Bronson bristles, barks and bites like a dangerous dog (“You just pissed on a gypsy in the middle of nowhere, that’s hardly the hottest ticket in town.”) You can pat the mongrel, but be wary, Peterson was renowned for biting that hand that fed him. Bronson is an acquired taste, like warm beer or black pudding.

Bronson is the kind of pure cinema that polarises audiences. Dramatically it falters on occasion, but the source material has furnished a fascinating tale, and there’s more than enough incident, detail and nuance of performance to lift the illegal game and place it on a subversive pedestal.