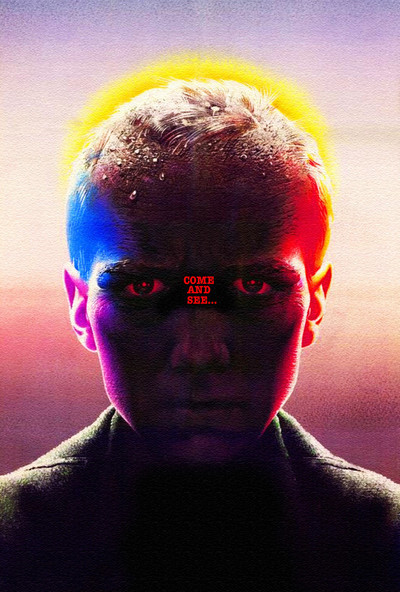

Idi i Smotri | Russia | 1985 | Directed by Elem Klimov

Logline: In Nazi-occupied Russia a peasant boy joins a group of partisan soldiers as they travel across a war-ravaged countryside.

“And when he had opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth beast say, Come and see. And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth.” --- Chapter 6, The Book of Revelation (The Apocalypse of St John the Divine), The New Testament

Without a doubt the most devastating and profoundly anti-war movie ever made, Elem Klimov’s semi-autobiographical account of a teenage boy unwillingly thrust into the atrocities of war in WWII Byelorussia (Belarus), fighting for a hopelessly unequipped resistance movement against the ruthless Nazi fascist forces, witnessing scenes of abject horror, as he slowly loses his innocence, inexorably loses his mind, his face eventually resembling that of a frightened old man, his soul finally a ruined sentinel. Come and See is the unfettered poetry of hell on earth.

Come and See (the literal Russian translation is Go and Look) follows adolescent Florya (Aleksey Kravchenko), a Belarusian villager, on a dark odyssey set in 1943. In the movie’s prologue he is fooling around with a young boy on the sand dunes, both pretending to be vigilant soldiers fending off the evil Germans. Florya uncovers a rifle amongst the military debris, his inspiration to fulfil a staunch patriotic stance and join the Soviet resistance. Later at his house with mother and two kid sisters the partisans arrive to collect him, much to the dismay of his mother, who has already lost her husband.

In a forest clearing Florya is integrated with the village comrades who have formed the small ragtag resistance, but his tattered boots result in him being left behind as a reserve. Disappointed Florya wanders off and meets Glasha (Olga Mironova), a pretty, slightly older girl, who appears touched, in love with a partisan commander. Florya and Glasha spend moments together, finding pockets of beauty and laughter amidst the trees and a light rain, but a sudden bombing destroys the brief tranquility, causing temporary deafness, and sends Florya and Glasha back to his family abode where true horror presents itself, and the two teenagers are forced to flee for their lives, through a hellish swamp, and into the midst of the terrorised survivors of the village. Florya’s interpersonal nightmare has only just begun…

Klimov wrote the powerful story many years before it was made. Taking inspiration from a novel called Story of Khatyn by Ales Adamovich, combined with his own wartime experiences, witnessing the atrocities of the Nazis, Klimov and Adamovich penned a script titled Kill Hitler. They were forced by authorities to drop the Hitler reference, even though the intent of the title was suggesting that one should kill a Hitler – demon - within you to prevent the worst. Taking their new title directly from The New Testament’s Book of Revelation, they fashioned an episodic journey of discovery and resignation, atrocity and genocide, and the screenplay was filmed in chronological order. The central character of Florya, who is in almost every scene, becomes a metaphorical vessel, the innocence that is blackened and defiled, left looking like a battered old man by story’s end. His character represents his entire people.

WARNING! FOLLOWING PARAGRAPH CONTAINS SPOILERS!

In a scene near movie’s end Florya is approached by a young woman in a daze whom he had left much earlier on with the other villagers (she looks so similar to Glasha that perhaps it is Florya's memory of her superimposed). The woman’s lips are torn, blood runs down her thighs. She had had managed to escape the burning barn with her baby only to be brutally gang raped and beaten terribly. To Florya (and to the audience) she represents the ruined beauty of love and life, as Glasha had told Florya of her desire to have children. The image is seared onto the retina, just as the final moments of the movie are forever imprinted in the mind’s eye. Seeing a framed photo of Hitler, cracked, lying in a muddy puddle, Florya takes his rifle and begins firing into the picture, and as he does so WWII archival footage and images burst across the screen, playing in reverse, regressing in time: corpses in the concentration camps, der Führer congratulating a German boy, 1930s Nazi party congresses, Hitler's combat service in WWI, Adolf as a schoolboy; and finally a portrait of the infant in his mother's lap … Florya stares hard into the innocent face of the baby, eyes glazing over, staring into the camera … Into the abyss.

Captured with astonishing realism (and shot in 1.33:1 ratio), yet infused with flashes of the surreal, director Klimov’s bold statement is without a doubt the most disturbing war movie ever made. It is also happens to be one of the most mesmerising, and how it balances this contrast of aesthetics - beauty and grotesquerie - is brilliant. There is a streak of absurdist humour and clever use of irony that winks slyly at the audience from time to time, with characters often talking directly to camera as they converse with each other. There is the moody, ambient synthesizer score, and hypnotic use of Steadicam (which much of the movie was filmed with), both of which add a curious, modern sensibility, but not incongruous. Come and See is state of the art filmmaking, yet unpretentious, never once feeling contrived, or bombastic. Many of the uniforms were original, and (much to the horror of Hollywood) real ammunition was used in some scenes!

Klimov doesn’t shy from the ghastliness of war; characters are blown to bloody bits, burnt beyond recognition, and in the movie’s most harrowing, and prolonged, sequence, an entire village is forced into a wooden barn and burned alive as the Nazi soldiers and officers gather around and admire their handiwork like its an exhibition for their amusement. Everything that happens on screen really occurred. Six-hundred-and-twenty-eight villages, with all their inhabitants, were burned to the ground. The wretched Holocaust tears at the very core of humanity. In an interview Klimov stated how the sense memory of that appalling horror carried through the generations of Belarusians, making it difficult for the actors having to recreate the war crimes that destroyed their people.

The performance of young Aleksey Kraychencko is nothing short of miraculous - apparently his hair going grey during the shoot! But I tilt my cap to Olga Mironova, and to the rest of the support cast, all of them delivering exceptional performances. Oleg Yanchenko’s stunning original music is integral to the movie’s intense atmosphere, and a few sourced pieces are used to superb effect; Strauss’s The Blue Danube, Wagner’s Tannhåuser overture, and finally, hauntingly, the Lacrimosa from Mozart’s Requiem. The entire movie can be seen and heard as a series of funereal movements dressed with suitably sombre and sobering images and sound.

Indeed, after viewing Come and See one is never the same. It is a tenebrous and monumental work, a deeply-etched, expressionist tour-de-force, a masterpiece of cinema.

Elem Klimov never directed again. His work was done.