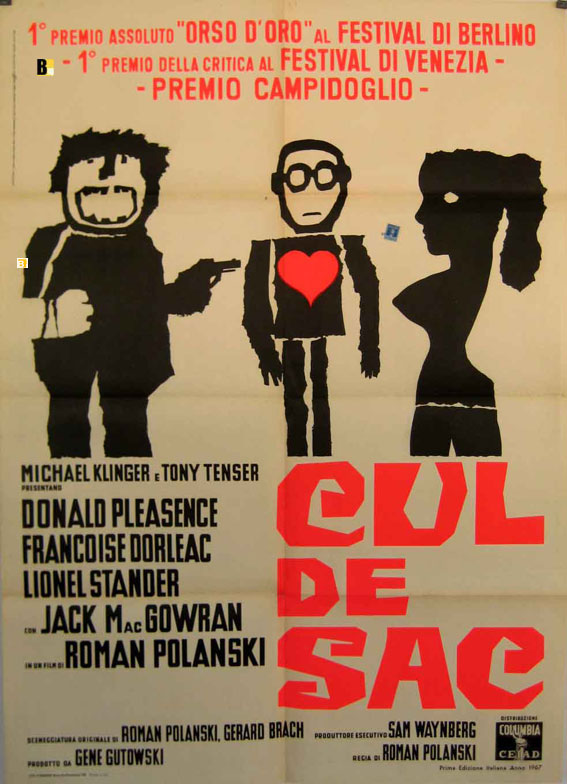

UK | 1966 | Directed by Roman Polanski

Logline: On an isolated beach castle property an eccentric husband and his wayward wife are set upon and driven to distraction by a desperate gangster and his befuddled accomplice.

“Here we are!” ... “Where?” ... “In this shit…”

A dark comedy of manners and errors, this is minimalist Kafkaesque perfection from Polanksi and his frequent co-screenwriter Gerard Brach. Cul-De-Sac means “bottom of the bag”, or “dead end”, and that is precisely where this movie begins and ends. There are no practical solutions, only anguish, despair, betrayal, and heartache, but shot through with an existential angst and muse that is sheer brilliance. It is apparently Polanski’s personal favourite, and it has been in my top ten favourite movies of all-time for as long as I can remember.

Two incompetent, injured gangsters on the run, Richard (Lionel Stander) and Albie (Jack MacGowran), find themselves on the sandy road leading to Northumberland’s Holy Island of Lindisfarne, where a beautiful castle property is perched. The tide is not their friend, and soon enough their car is waterlogged and immobile. Dick must seek assistance, as his friend and colleague is badly wounded, so he heads off to get help from the castle owners, who happen to be the meek and eccentric George (Donald Pleasence) and his young, mischievous wife Teresa (Françoise Dorléac).

Before long there is a strange and amusing power play going on between Dick, George, and Teresa. Dick has arranged for his boss, Mr. Katelbach, to come and collect them, but visiting friends of George’s, including a secret lover of Teresa’s, get in the way. It’s a weekend of situations, to say the least.

The superb black and white cinematography is by English veteran Gilbert Taylor (who had already shot Polanski’s Repulsion, made back-to-back with Cul-De-Sac, and would shoot Macbeth for him a few years later). Knowing how much friction Taylor had with George Lucas, ten years later on Star Wars, it’s curious how Polanski and he worked together, knowing just how much Polanski has control of his movies’ composition and mise-en-scene.

Brach and Polanski’s screenplay is a playful riff on Waiting for Godot (in fact, a working title of the movie was When Katelbach Comes). Most of the humour is not in actual gags, but in the subtle nuances of character, and it is undeniably one of Polanski’s richest, in terms of character and characterisation. It forms a curious relationship with his debut feature, Knife on the Water, which deals with the power play between three people on a yacht. There is a very similar atmosphere, even though Cul-De-Sac is less of a thriller, though it does feature some thrilling moments.

Donald Pleasance is exceptional as the awkward George, slowing losing his grip. It’s an early career performance, but, that said, he is challenged every step of the way by the gruff charisma of Lionel Stander, who chews the scenery with a veritable chomp. The two men, as mannered and idiosyncratic as they are, deliver one of the finest comedic counterpoints in cinema history. It’s an absolute joy to watch them rub up against each other, whilst Françoise Dorléac (Catherine Deneuve’s elder sister, who was tragically killed in a car crash a year later) slithers around like a delicious serpent, the ivy to make the men itch further, and for the trainspotters, there’s a very young Jacqueline Bisset, hiding behind sunglasses.

Cul-De-Sac is one of those movies I can watch again and again; a fifty-year-old movie whose tone, mood, atmosphere, visual style, and performances are pure cinematic pleasure. A masterful collection of odd moments as rewarding and bewildering as the best dreams.