US | 1978 | Directed by George A. Romero

Logline: Two soldiers, a reporter, and his girlfriend seek refuge in a shopping mall from a zombie pandemic, but battle to survive.

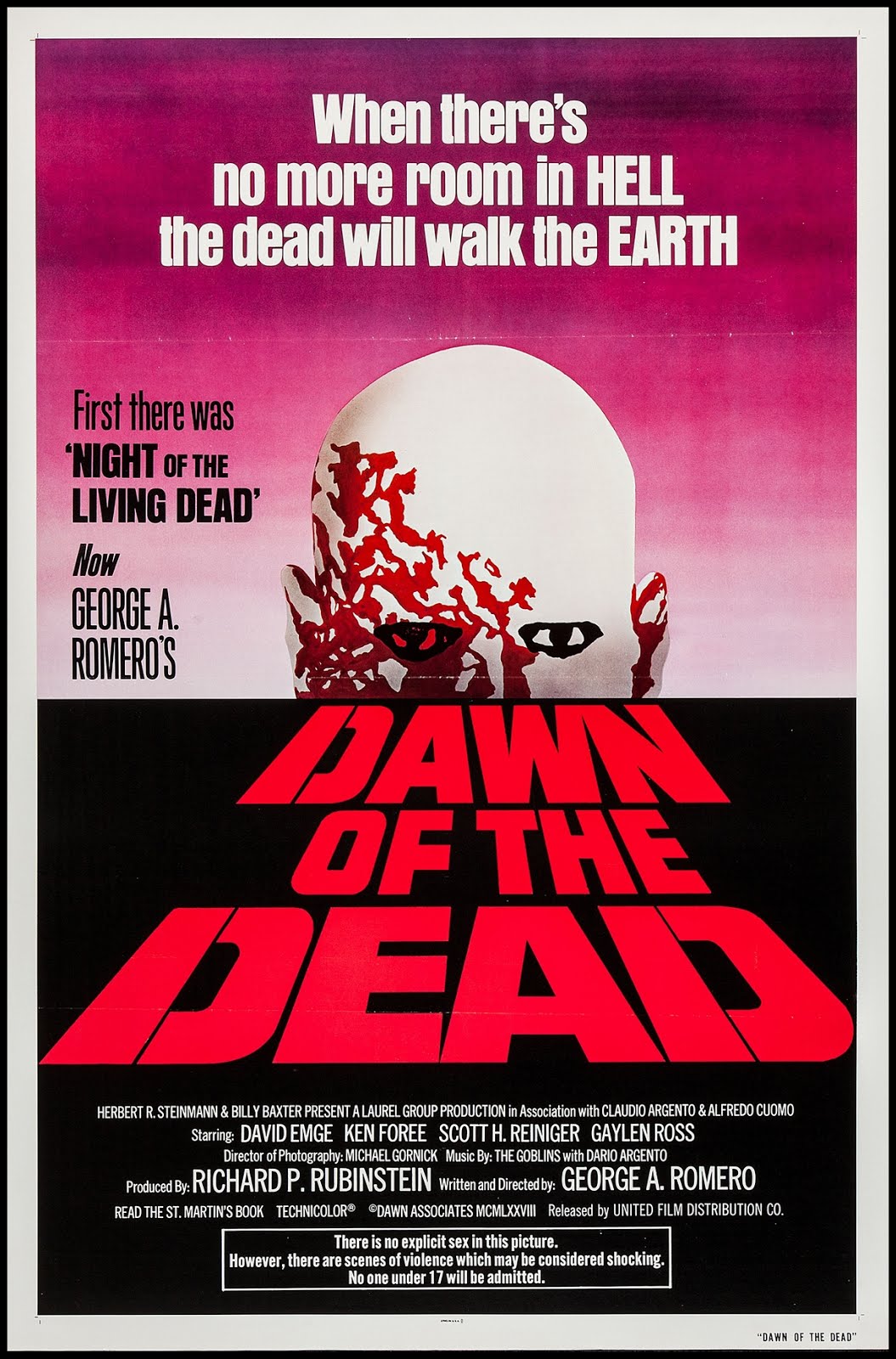

“When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.” One of the most memorable and enduring taglines in modern horror history to one of the most regularly discussed and championed modern horror movies in history. Romero’s sequel to his landmark zombie flick Night of the Living Dead cut down all the competition like a point blank shotgun blast to the head. There hadn’t been a graphic horror movie with such a relentless tone, such a scathing satirical edge, like this consumer mayhem.

The movie opens at a Philadelphia television station where everything is under pressure. It seems the plague of the walking dead established in the first movie has escalated ten fold. Instead of rogue farmers armed with shotguns taking out whoever looks troublesome, it’s a SWAT team armed with M16s storming apartment blocks killing anything remotely disheveled and evacuating the odd lucky person.

Two of the station employees, traffic reporter Stephen (David Emge) and broadcast executive Francine (Gaylen Ross) meet up with Roger (Scott H. Reiniger) and Peter (Ken Foree), two SWAT soldiers who’ve deserted their posts, and together they steal a helicopter in order to escape the chaos. After flying west they land and seek shelter in an abandoned shopping mall complex outside of Pittsburgh to wait the apocalypse out. They barricade themselves into a small storeroom and clear any unwanted undead from the mall’s interior.

But tensions soon arise as the weeks drag on. Zombies linger outside the mall refusing to dissipate. Then a biker gang infiltrates the mall with their own brand of chaos. Looting and rampaging, chopping down zombies for the sheer hell of it, the wheeled marauders cause the movie’s protagonists further headaches. So it’s insult to injury as the four survivalists fend off the lethal bandits and the flesh-hungry zombies in droves, with any plans being scuttled.

To borrow a tagline from a fellow modern horror cult classic, “Who will survive, and what will be left of them?”

Dawn of the Dead was Romero’s sly stab at the rampant consumerism and apathetic discourse of modern America. Most of this thematic subtext went straight over the heads of Joe Average horror nut, but the critics got the score. Even if it is a parable on the subversive dangers of automatic living, it still has great bite as a gung-ho horror flick. Tom Savini’s special effects make-up serves up some ingeniously staged gore. The blood looks like paint, but hey, that didn’t prevent Argento’s early movies from being so beloved. Two of the most memorable gore effects sequences are the zombie having the top of his head whacked clean off by a helicopter rotary blade, and a biker (played by Savini) cleaving a machete into the side of a zombie’s head. Both simply executed, but gorgeously effective.

Dario Argento’s brother Claudio produced the movie and Dario was given the opportunity to re-cut the movie for European audiences. His version was shorter, deleted all “funny scenes” and kept the movie more action-orientated, whereas Romero’s had more humour, longer dialogue scenes, and was considered more horror-orientated. In Australasia and the UK the movie was titled Zombies: Dawn of the Dead. In New Zealand it was given the then unprecedented censorship rating of R18 – Contains Frequent Episodes of Graphic Violence. I have fond memories as an eleven-year-old of a huge mural based on the poster art in the foyer of the Majestic Cinema in my hometown of Wellington, and being in awe of the art, tagline, and that truly "adult" classification (as most horrors at the time were classified R13 or R16).

To make matters entirely confusing for international audiences Italian distributors re-titled it Zombi, so then Lucio Fulci’s 1979 zombie island opus was given the title Zombi 2 to cash in on Romero’s success. Fulci’s flick was called Zombie in the States, and Zombie Flesh Eaters in the UK and down under.

While Dawn of the Dead doesn’t have the urgent, cinema verité, docu-drama atmosphere of Night of the Living Dead, or the higher production values, better performances, and utterly convincing viscera of Day of the Dead or Land of the Dead, it’s a genuinely effective, satirical date stamp. Less creepy than Night, less chilling than Day, but the grim, apocalyptic tone is firmly in place, the despair locked and loaded, the ghoulish resonance deep, dark, and damp with dread.