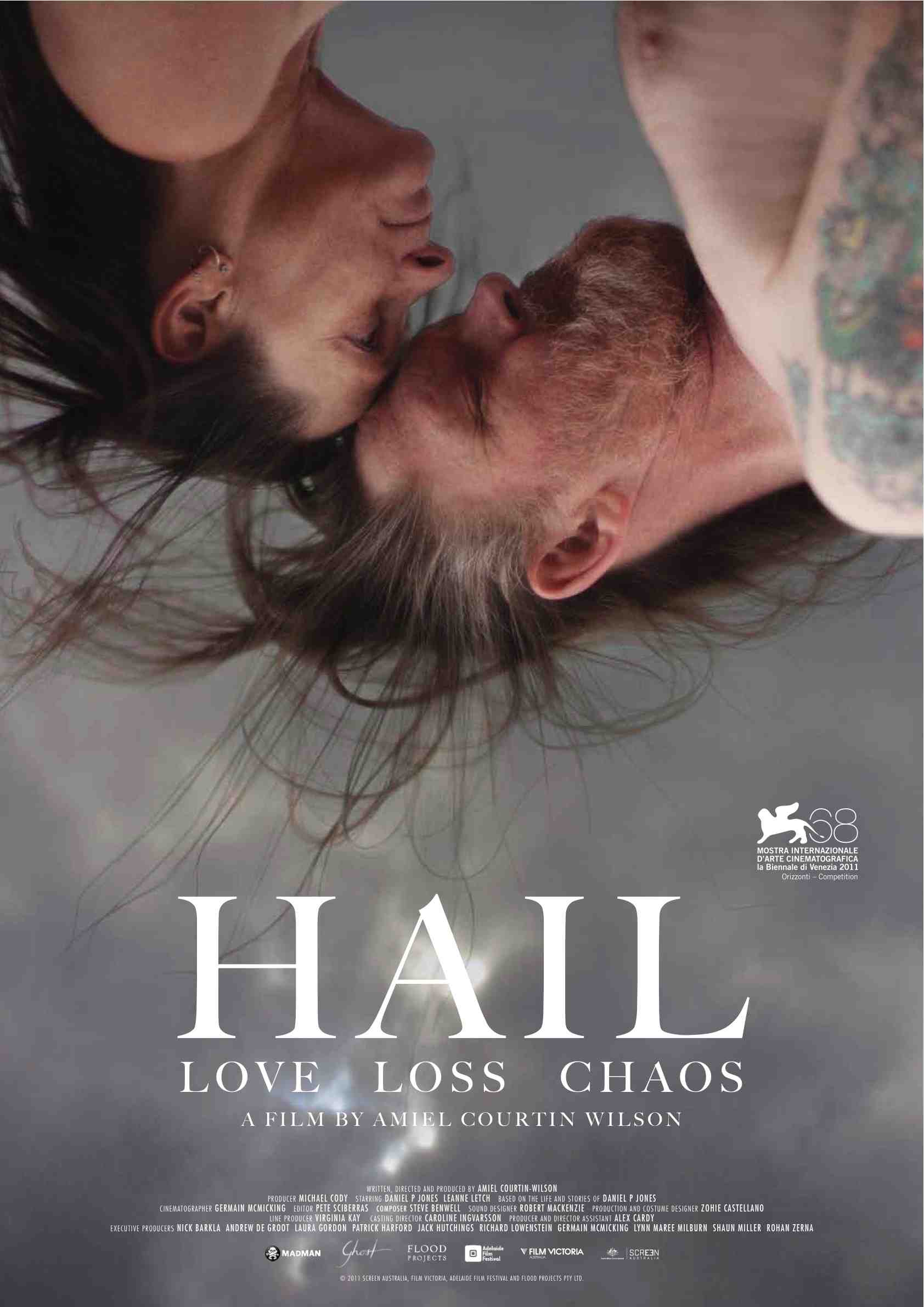

2010 | Australia | Directed by Amiel Courtin-Wilson

Logline: A world-weary criminal is released from prison and reunites with the love of his life, but finds he cannot escape his inner demons, the trappings of crime, and the all-consuming spectre of tragedy.

Hail is the kind of movie that only comes along once in a dark blue moon; a tour-de-force of visual poetry, visceral emotion, and dizzying psychological intensity, yet is delivered in an intimate, but distinctly expressionist style. This is a movie of contradictions and abstraction, a raw and powerful indictment of unbridled love and rage, as out of control and indulgent as it is stripped back and honest. Hail rains down like a force of pure cinema, dramatic and uncompromising.

This is a docu-drama unlike anything you’ve seen before, certainly nothing like this has come out of Australia, and even more extraordinary is that it is the director’s first feature (having worked prior on documentaries and shorts). Basing the threads of his narrative on the stories and life experiences of lead actor Daniel P. Johns (who essentially plays himself) Amiel Courtin-Wilson (just thirty years young, but exuding the directorial maturity of someone much older and wiser) has constructed an awesome picture that deals openly and corrosively with the poison of love and hate, each organic imbibed in different doses.

Shooting on 16mm cinematographer Germain McMicking has achieved some truly astounding imagery especially in the movie’s second half when the mise-en-scene becomes entrenched in Daniel’s grief and wrath absorbing and reflecting as visual metaphor and symbolic motifs. The director favours the use of extreme close-up. One image in particular will haunt me for years to come, I’m sure; that of a dead horse plummeting to earth, the wind buffeting its neck and legs giving the illusion that the creature was still alive and writhing in abject terror.

The performances, that of 50-year-old Daniel P. Johns and his lover Leanne Letch (both of them born on the same day, month and year), are exceptional. Whilst Daniel has had acting experience with Plan B (a theatre group made up of ex-cons) Leanne had never acted before in her life. Their naturalism imbues the movie with an honesty that is profoundly affecting. The movie balances the grotesque with beautiful. Daniel and Leanne live on the fringes of society, and it is the sharp darkness that lurks close to those edges that frequently scratches, and can cut deep, sometimes to the bone.

The source music is inspired, but it is the spectacular sound design courtesy of Robert MacKenzie that pushes Hail into an audio experience league of its own. One doesn’t hear this kind of experimental assault on the senses very often, combined with Amiel Courtin-Wilson and Germain McMicking’s visuals, and the editing of Peter Sciberras, it is truly powerful, and resonates like a dream-soaked-nightmare.

One must surrender to Hail and allow Daniel’s journey of hope and promise that spirals into the darkness and violence of his despair and confusion to engulf and overwhelm you. There is reward; a genuine sense of inspiration from the uncompromised artistry of the director, his muse, and his collaborators. Hail takes no prisoners, let the elements be.