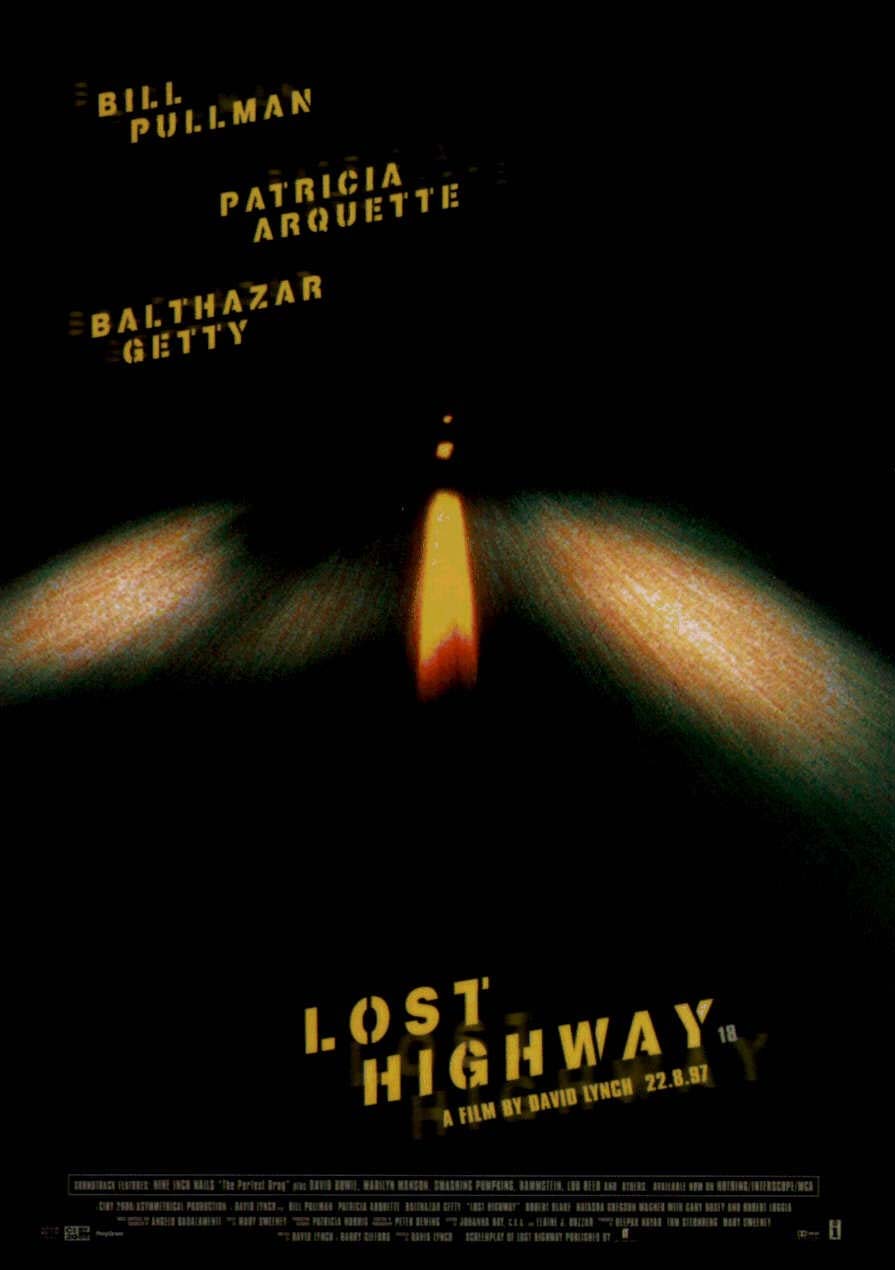

US | 1997 | Directed by David Lynch

Logline: A jealous musician seemingly murders his wife, the psychological consequences of which plague him so severely he suffers a psychogenic fugue.

“Dick Laurent is dead.”

Whatever conclusion you arrive at, there’ll still be several pieces that don’t fit the puzzle, and that’s just how David Lynch and co-screenwriter Barry Gifford want it. This is the dark side of the road, the section of gravel between the hot asphalt and the ragged grass; this is the black magic hour. Fire walk with me and I’ll show you the way inside the Black Lodge.

Indeed, Lynch has confirmed that the world of Twin Peaks and the world of Lost Highway are one and the same. It is in this world of false beauty and genuine evil that Fred (Bill Pullman) and Pete (Balthazar Getty) and Renee and Alice (both Patricia Arquette) exist. It is also the same underworld where Mr. Eddy and Dick Laurent (both Robert Loggia) dwell. And the same limbo where the Mystery Man (Robert Blake) floats and asks the question, “We’ve met before, haven’t we?”

Lost Highway operates like a supernatural film noir dream. Of course, this can be said of most of David Lynch’s movies. He hates to explain them, instead offering vague, often cryptic, explanations, or more precisely clues. If Lynch hadn’t become a film director I’m sure he would have made a great illusionist. Of course he paints, and his ciné palette is one of the most alluring of contemporary American filmmakers.

David Lynch dislikes documenting events on video, preferring to remember the moment and recollecting in his own way, not necessarily the way it happened. This is the essence – or at least one of the essences, for Lost Highway has many off-ramps – of the movie. Identity becomes blurred just as memories implode. Circumstance becomes crucial, yet remains elusive.

Lynch described his movie Eraserhead as “A dream of dark and troubling things.” An apt description for For Lost Highway of which he simply calls “A psychogenic fugue”; which is a dissociative order where an individual forgets who they are and embarks on a new life. Their perception and elements of their consciousness are impaired and if they recover they almost never retain any memory of the fugue period.

Lost Highway is packed full of loaded symbolism, metaphors, clues, narrative booby traps, and probably a couple of red herrings for good measure. The narrative relies almost exclusively on the mise-en-scene, and the plot plays second fiddle. There is definitely a prologue and an epilogue, and significantly the ending and the beginning aren’t necessarily the finish and the start. Lynch loves toying with time and space, and his most curious movies indulge in this without compromise: Eraserhead, Dune, Twin Peaks television series, Mulholland Drive, and more recently Inland Empire.

There is a jarring garish quality to Lost Highway, an aesthetic that I liken to Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. They are very different films, but they command with a similar raw energy; very designed, very deliberate, creepy and grotesque, sensual and provocative. They both glide across the same strange carpet. But while they both court surrealism Lost HIghway beds down with the bizarre.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Jack Torrence visited the Black Lodge as well.

The soundtrack – music and sound – is always imperative in a David Lynch movie and joining Angelo Badalamenti’s dreamy score are moody songs from David Bowie, Nine Inch Nails, Rammstein, Lou Reed, and Marilyn Manson. The call girl dances with the Devil in the pale moonlight. Be careful what you desire … and whom you trust; some lies are improvised, others were born evil.

“Dick Laurent is dead.”