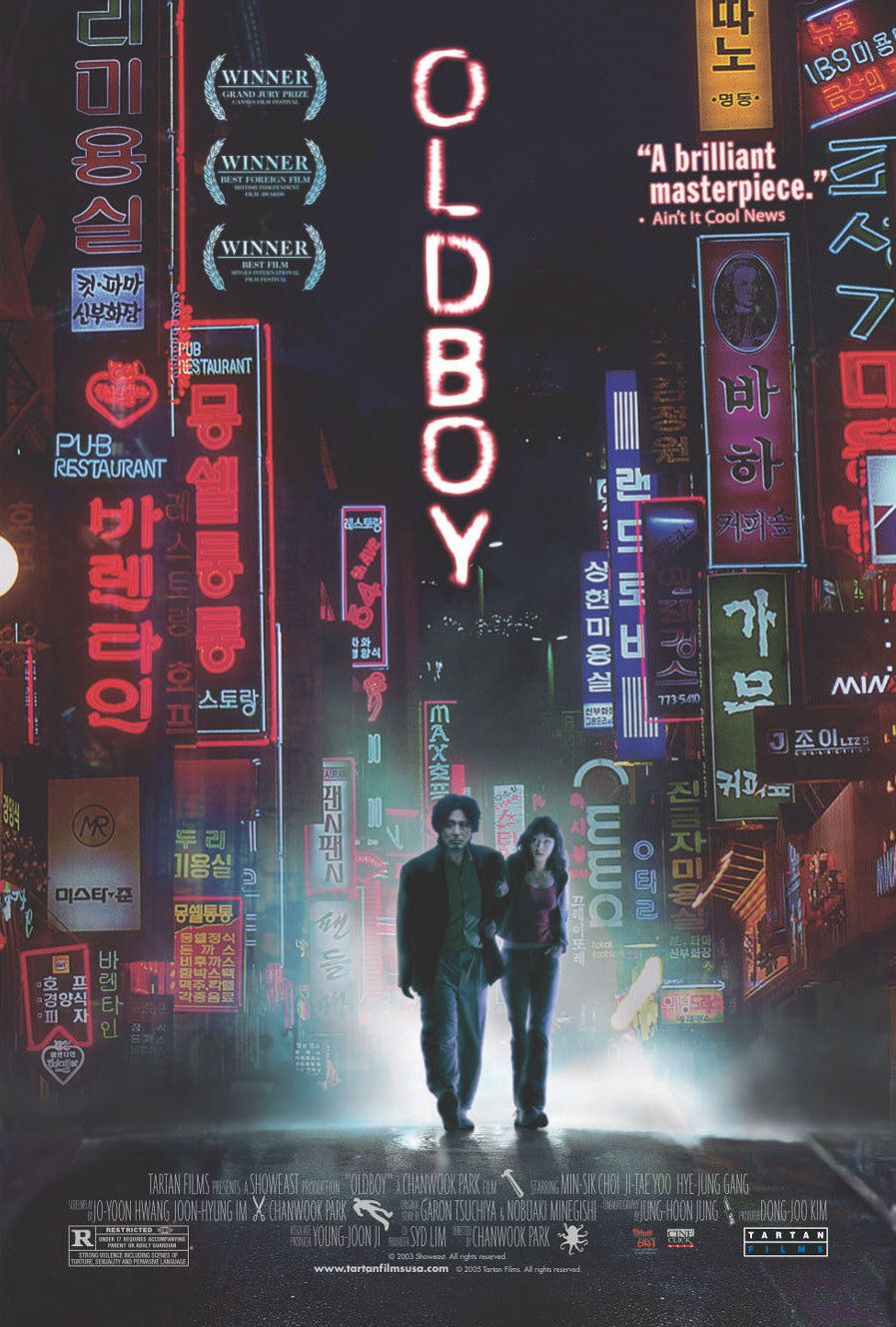

South Korea | 2003 | Directed by Chan-wook Park

Logline: An ordinary man is kidnapped and imprisoned for fifteen years, then suddenly released, confused and bewildered, only to be informed he must find his captor in five days.

“Laugh and the world laughs with you. Weep and you weep alone.”

Adapted for the screen from a Manga comic, Oldboy is a tour-de-force of cinematic storytelling, a stunning darkly poetic vision of identity and revenge. It is not for the prudish, nor is it for the squeamish, as it burns itself onto your weary retina and scalds itself through your tender skin like a nightmare dream of grotesque beauty.

It is the middle installment in the director’s revenge trilogy (after Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance and before Kindhearted Ms Guem-Jar AKA Lady Vengeance); however its story is completely self-contained. It begins part-way through its story, and later we return to this scene, and it the movie finishes amidst the alpine pine and snow of New Zealand’s magisterial Southern Alps.

Min-sik Choi is brilliant as the tortured soul Dae-su Oh, an ordinary businessman who is abducted and held prisoner for fifteen years, never once meeting his kidnappers. Then as swiftly as he was first abducted, he’s released. The world has changed, and so has Dae-su. But he has a mission bursting inside of him. Along the way he meets a young bartender, Mi-do (Hye-Jeoung Kang), who takes pity on his plight and desperate quest, only to find herself slipping in over her head (as much as Dae-su is drowning in the deep end of a dark mystery).

Woo-jin Lee (Ji-tae Yu, quietly exceptional) is the mystery man, the man who seems to hold the answers to Dae-su’s questions, but not without running a gauntlet. Dae-su finds himself in a predicament with only five days to solve the reasoning of his imprisonment. Dae-su realizes he must plunder the past to uncover the truth. But some truths cut deeper than lies.

“Like the gazelle from the hand of the hunter, like the bird from the hand of the fowler, free yourself.”

Everything about Oldboy is beautifully constructed and executed; from the production design and art direction (at times highly stylised), to the editing and music. There are extreme moments (eating the live octopus) and scenes of graphic violence (most of which happens off-screen), but there’s a controlled chaos, a deliberate sense of order and symmetry. Oldboy ricochets with a fierce intelligence, despite its perverse machinations.

You can’t help but be impressed with a movie as provocative as this; both sensually and viscerally. A sense of humour exudes, oily and gleaming, glistening and congealing like the crimson blood spilled on the pristine marble floor of the villain’s penthouse. But just who is the villain and who is the hero? Who is the victim and who is the culprit? The character shades are grey like the timber wolf stalking the rabbit in the snow.

In 2004 Oldboy won the Jury Grand Prize at Cannes, was nominated for the Palm D’Or, and won Best Film at the renowned Sitges Festival in Spain. In its home country festival, the Grand Bell Awards it won Best Actor (Min-sik Choi), Best Director, Best Lighting, Best Music, and Best Editing. It went on to win a further ten international festival awards and another ten nominations.

Oldboy’s thematic treatment of vengeance suggests that revenge is a dish best left uneaten as it will only destroy everything. No one escapes unscathed; the collateral damage wrought by the wrath of vengeance is wickedly cruel. Cruelty, indeed, is a significant element within Oldboy. Irony, too, casts a long dark shadow. While the serenity of the movie’s final sequence in the snow only reinforces the tragedy of the tale; a tragedy borne from the double-edged sword of a reckless adolescent desire.