France/Denmark | 2013 | Directed Nicolas Winding Refn

Logline: An American criminal living in Thailand becomes embroiled in a high-stakes game of murder and vengeance when his criminal mother arrives to seek revenge over the slaying of her eldest son.

For his ninth feature the Danish tour-de-force that is NWR stirs up a stylised ultra-violent brew of spiced family dysfunction and exotic doom. Only God Forgives isn’t about religion or faith, it’s about broken love, lust askew, twisted vengeance, and it might just touch on that mercurial element known as redemption, but then, in the tenebrous realm of the foreign underworld, there’s no more room in heaven.

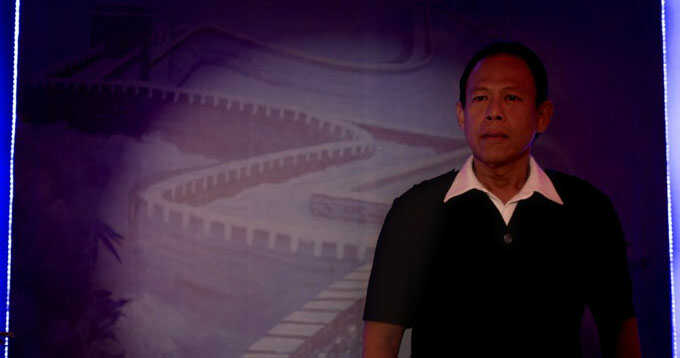

In the boxing ring of life sex and death dance a lonely waltz. Julian (Ryan Gosling) knows this well. His brother Billy is psychopathic, and his mother Crystal (Kristen Scott Thomas) is sociopathic, while his lover Mai (Yayaying Rhatha Phongam) is indifferent, and his nemesis Chang (Vithaya Pansingarm) cold-blooded. These are reptiles in human form.

The Bangkok of Only God Forgives is a sensual hell.

Booed at Cannes Film Festival Only God Forgives just won the Sydney Film Prize (awarded each year by the Sydney Film Festival in recognition of courageous, audacious, cutting edge cinema) – the second time for Refn – and cements itself as one of the year’s most intriguing movies.

Gosling, in a performance even more restrained than Drive (2011, Refn’s neo-noir box office hit), exudes the same seductive charisma that gives him a kind of early De Niro presence (something I’m sure hasn’t gone unnoticed by Refn a la Scorsese). He’s a troubled soul with demons scratching under his skin and skeletons just waiting to tumble from his closet.

Kristin Scott Thomas is almost unrecognizable as the matriarchal manipulator. If her sons Billy and Julian are bad eggs, then she’s most certainly the crooked hen that laid them. She has the social graces of a leopard in a rabbit hutch, and a tongue soiled long ago.

Cliff Martinez provides yet another stunning score of ethereal electronic lushness, dark, but uplifting; in particular a confrontation fight scene in the later half of the movie that throbs with an intensity that reminded me of classic Goblin (Argento’s favourite band).

Refn has made a brooding, dangerous, but incredibly seductive movie that writhes and coils like a snake finding a cool patch of stone on a hot day. The neo-washed filth of the Bangkok backstreets bathed in the under-glow of nighttime springs to life through Larry Smith’s vivid primal cinematography, the extreme violence contrasting in very Lynchian fashion with kitsch Thai pop music.

Yes, Only God Forgives is like David Lynch drinking Chang beer and discussing (im)morality with Martin Scorsese, whilst Dario Argento loiters in the background whispering perversities. Only God Forgives resonates long after the final scene, but there’s hollowness to its finale; Refn deliberately denying his audience the predicted avenue. There’s no clichés at work here, but the narrative cries – no it screams out - for the old way of the sword.

Only God Forgives screened as part of the 60th Sydney Film Festival.