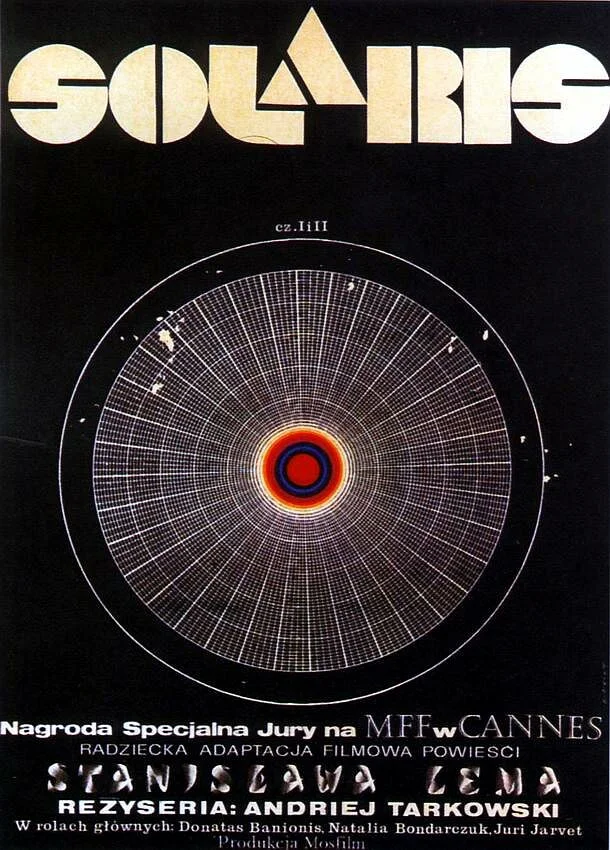

Solyaris | Soviet Union | 1972 | Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky

Logline: A psychologist is sent to a space station operating above the sentient oceanic planet Solaris to investigate the strange behaviour of its remaining two scientists, and is bewildered when he is visited by his wife, who committed suicide years earlier.

One of the most philosophical, perplexing and haunting science fictions ever made, often compared to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, but more in tone and feeling with Chris Marker’s extraordinary muse on memory, guilt and desire, La Jetée, Solaris is a visually hypnotic and oneiric study of loneliness and quiet desperation, a metaphysical portrait of the human mind from the perspective of the alien … or perhaps the other way around?

Based on the brilliant 1961 novel of the same name by Polish author Stanislaw Lem, yet screenwriters Fridrihk Gorenshtein and director Tarkovsky added a key element; the narrative prologue set on Earth where cosmonaut psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis) visits his home to say farewell to his father and watches archival footage of cosmonaut Berton (Vladislav Dvorzhetsky)’s official hearing over the death of another cosmonaut who vanished on the surface of Solaris. Solaristics (the on-going study of the living planet) has revealed that the human endeavours in understanding this incredibly advanced alien life form are proving potentially futile.

Novelist Lem (who apparently hated the movie, especially what he saw as sexual perversity) went to great lengths to describe that human science was unable to properly handle a truly alien life form; that it would be beyond human understanding. Tarkovsky, however chose to focus on Kelvin’s feelings towards his wife, Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk), his guilt over her death, and the effect space exploration has on the human condition.

In the movie Dr. Snaut (Juri Javet) says “We don’t need other worlds. We need mirrors.” It’s a powerful statement that ricochets in the mind. Essentially human kind is a naïve race, embroiled in our own psychological and emotional stew, and perhaps ultimately not intelligent enough to be dabbling the way we do, and will continue to do, with the cosmos. That’s not to say space exploration is out of bounds, but intelligent alien life may very well be our psychic undoing.

Both Lem and Tarkovsky’s intent is partly to show that we can only ever understand the universe in human terms, and even if we are presented with something ineffably strange we will inevitably humanise it. Nearly every science fiction movie that deals with an alien life gives it a form and/or personality based on something familiar on Earth, and that is an incredibly narrow-minded school of thought.

The concept of the alien planet physically manifesting the memories and fantasies of the humans who are in close proximity to its surface is an extraordinary idea, and especially fascinating is Hari’s contrasting warmth and fragility, returning to plague Kelvin in slightly different versions. It is this “spectral physicality” concept that prevails and provides the movie with its provocative, revelatory end, which is fantastic as it is deeply melancholic.

The movie is restrained in its use of special effects, but the end result transcends any limitations. Tarkosvky was adamant not have the movie tied to genre; to have a science fiction film that meant more than its generic trappings in terms of its humanity. Still, the movie’s production design is excellent in conveying the desolate and dissolute state of the space station. Kelvin, Snaut and Dr. Sartorius (Anatoli Solonitsyn) are disheveled and sweaty, and space station cluttered, yet hollow (Ridley Scott must have been influenced somewhat when he made Alien).

Solaris is very long (nearly three hours) and very languid in its visual narrative (Tarkovsky always preferred long takes, lingering gazes; the moment within the moment), so it is a demanding film. It’s not as experimental as his two later movies, The Mirror or Stalker, not as epic as his earlier Andrei Rublev, or as intimate as his last movie The Sacrifice, but in an elusive, strangely affecting way Solaris is his most satisfying movie (ironically Tarkovsky considered it his least favourite).

Steven Soderbergh made a surprisingly decent, atmospheric remake in 2002, starring George Clooney as Kelvin and Natasha McElhone as Rheya (changed from Hari).