Japan | 1993 | Directed by Takashi Kitano

Logline: A jaded, but suspicious Yakuza in Tokyo is assigned to take his men to Okinawa to help settle a dispute between two factions, but several of his men are killed, so he retreats to a remote beach to contemplate the situation and plan his revenge.

Beat Kitano, as he’s nicknamed, has been making his own brand of mob movies since the late 80s. Minimal, with a deadpan comedic edge, his style of realism is laced with a poetic undertone. It is with Sonatine that his preoccupation with the themes of loyalty and honour, and his penchant for sudden extreme violence come to a spearhead. The title refers to a style of folk music associated with the Okinawa region.

Kitano (who nearly always features in his own movies) plays Murakawa, the world-weary Yakuza who is embroiled in a series of incidents leading to a set-up to take him out of the powerful gang equation. It’s not until he has taken shelter at an isolated coastal property with his remaining clan that Murakawa takes stock of his predicament and slowly, but surely lays the obtuse foundations for retaliation.

Sonatine plays with rhythms, and pulses with a steady heartbeat of implicit violence that occasionally explodes with rage. There is vivid colour and spreading darkness in equal measures. Kitano doesn’t have all his cards on the table; he has a few aces up his sleeves, but you never know when you’ll whip them out. Just as his violence is unpredictable, so is his eccentric sense of humour.

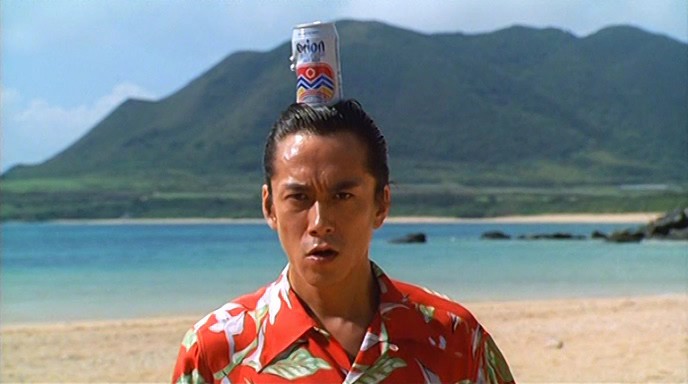

Joe Hisaishi’s melancholic score is highly memorable, which frequently marries magnificently with Kitano’s stark and lonely visual narrative. I must make mention here of the striking movie poster which has lingered with me ever since I first saw it at the Wellington Film Festival when the movie was first released; it’s a brutal, yet strangely beautiful, and iconic image which seems to work both existentially and metaphorically.

Kitano’s movies rarely finish on a rounded or uplifting mood, and Sonatine is no exception. The tone of the movie is detached, yet it is also one of his most affecting movies. Murakawa is arguably one of Kitano’s most sympathetic roles, despite his inherent fatalism and nihilistic approach to life. In one of the movie’s many memorable scenes – possibly even the movie’s penultimate moment – Murakawa forces his two closest gang members to play Russian roulette after he watches them playing silly William Tell buggers compounding the fragility of life.

Sonatine is the gangster movie twice removed; a left-field transgression that bears much of the genre’s traits yet takes side-steps and behaves like a wild card. It satisfies, yet infuriates, it rewards, but leaves a bitter taste in the mouth. Ultimately the movie remains stoic and disquieting; the ironic resolution of gangster life is played to the hilt.