Dekalog | Poland | 1989 | Directed by Krzystof Kieslowski

Logline: Ten modern fables loosely based on each of the Ten Commandments, all set within different apartments in the same high-rise block.

When Polish filmmaker was commissioned to make a series of hour-long dramas for Polish television little did he know the impact his work would have on cinephiles and dramatists around the world for years to come. In fact, Stanley Kubrick described The Decalogue as the only masterpiece he could name in his lifetime. Now, that’s a compliment!

Dealing directly with the emotional turmoil suffered by humanity, when instinctual acts and morality conflict, when the pressures of society burden and overwhelm, when the little ironies and bittersweet joys and sorrows of life’s rich tapestry connect and disconnect, the tales told within the framework of The Decalogue are universal, but with a quiet (and disquieting) religious zeal. The stories may be based on each of the Old Testament’s Ten Commandments, but in the bigger picture – and more importantly – they are about the very fabric of our emotional and psychological being. At their very basic these ten tales are about life and death, love and acceptance, confusion and betrayal.

Each of the perfectly-pitched screenplays are co-written between Kieslowski and long-time collaborater Krzystof Piesiewicz, who co-wrote the masterful Three Colours trilogy with Kieslowski, as well as the melancholic Double Life of Veronique, and the Heaven/Hell/Purgatory trilogy which was to be directed by Kieslowski before his untimely death. A number of different cinematographers were employed, including Piotr Sobocinski (Three Colours: Red) and Slawomir Idziak (Three Colours: Blue), but each of them maintains a key palette and Kieswlowski’s distinct visual grammar.

The sombre, austere tone (with the exception of The Decalogue 10) and narrative efficiency of the series is firmly established in The Decalogue 1: “Thou shalt have no other Gods before me”, and it’s also one of the stand-out episodes: A university professor trains his young son in the use of reason and scientific method, using a computer to analyse data and predict circumstance. The boy’s aunt worries he is neglecting his spiritual education. The ten-year-old boy is delighted when he is given ice-skates for Christmas, especially since the computer delivered data stating the frozen lake beside the house was safe to skate on …

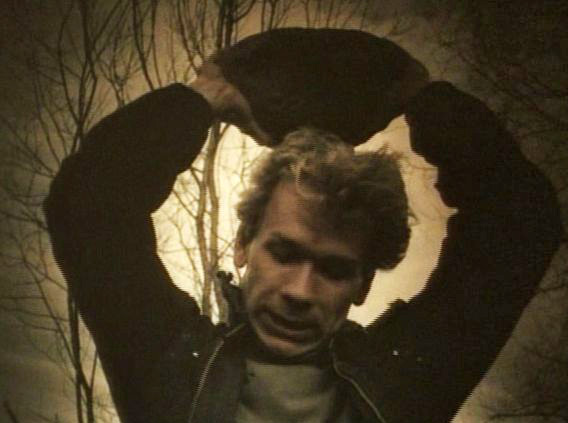

The entire cast is excellent, each tale only uses a handful of actors, some of which appear in more than one episode, with a mysterious figure (a young man) appearing in all of them as a kind of heavenly observer. His role changes in each of the episodes he’s in, but always a silent bystander of sorts, and his repeated presence is never properly explained .Two of the most powerful episodes (5 & 6) were completed as feature-length movies the previous year and released as A Short Film About Killing (“Thou shalt not kill”) and A Short Film About Love (“Thou shalt not commit adultery”). Both episodes were truncated for inclusion in the television series with Love having a different ending, but still retain all the dramatic and poetic potency.

Kieslowski’s subtlety and beautifully-balanced nuances of storytelling are a testament to the power of visual storytelling within the constraints of television (all episodes are shot in the 1:33.1 ratio). He delivers delicate, yet hugely dynamic elements with the hand of a consummate artist, never a shot or line of dialogue feeling out of place. There are few directors who commanded the level of respect Kieslowski garnered in the years following The Decalogue up to his death in 1996. Although curiously (and bemusedly) he saw himself as only a so-so director, content to puff on his pipe, and relax in a big armchair. It’s a shame that he died before being able to complete his final project, and his early passing was a great loss to world cinema.