USA | 1985 | Directed by William Friedkin

Logline: A Federal Secret Service Treasury agent becomes recklessly obsessed with bringing a dangerous counterfeiter to justice after the criminal has his older agent partner murdered.

This was the quintessential 80s cop thriller; fast-paced, action-packed, violent, and profane, but more importantly, unpredictable, uncompromising, and that Wang Chung soundtrack. William Friedkin was back on the streets delivering the other side of the coin to his seminal NYC cop thriller, The French Connection, and it’s vibrancy holds steadfast.

Director Michael Mann tried unsuccessfully to sue Friedkin for ripping off his Miami Vice concept, but apart from the torrid urgency and a throbbing synth soundtrack, Mann was clutching at straws. Sure, Miami Vice was slick and provocative, but it was television; it simply wasn’t anywhere near as dangerous or volatile as Friedkin’s adaptation of Gerald Petievich’s incendiary novel.

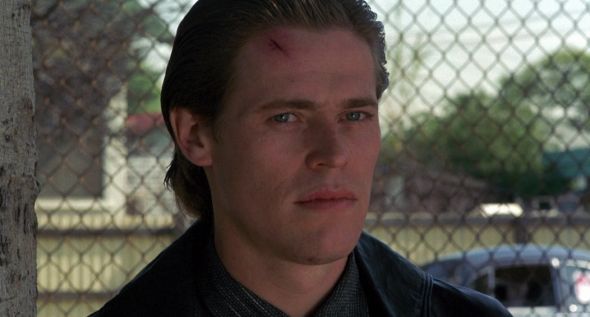

William S. Peterson’s performance as treasury agent Richard Chance is blistering. He’s a determined asshole, treats his informant girlfriend like shit, and throws tantrums whenever something doesn’t go his way. But somehow the audience cares for him, or at the very least we want him to succeed. Willem Dafoe as his nemesis, the cool, calculating, creepy Eric “Rick” Masters, is a deadly creature. Furiously talented, both as an artist and as a counterfeiter (the montage sequence of Masters making the fake paper is brilliantly authentic), Masters is also a hit with the ladies, and he treats them real nice.

Chance’s new partner John Vukovich (John Pankow) is the nervous type, but he’s up for the mission, and it’s a crooked trail they’re on. As it turns out these boys are well above the law, and they’re up to their eyeballs in bureaucracy. It’s as if the City of Angels is treating them like Lucifer’s little helpers. Masters is always one step ahead, and they’re falling behind.

The fiery palette is courtesy of masterful cinematographer Robby Muller, and much of his location camerawork is astonishing. The extraordinary car chase scene that ends up with Chance driving down a motorway the wrong way has to be seen to be believed; Friedkin actually gives his own amazing car chase under the railway from The French Connection a run for its money! Meanwhile the sweat pours from the actors, and perspiration builds like a film over the audience.

But there is a curious subtext at work through the movie; a homoerotic element. In fact there are numerous gay/lesbian references not only in dialogue, but also imagery, not usually seen in such highbrow Hollywood fare. In many of Friedkin’s movies his characters display a misogynistic streak, yet conversely his movie Cruising was heavily criticised for his strange treatment of the New York underground gay scene, and yet Friedkin's earliest lauded movie is the gay stage adaptation The Boys in the Band.

Friedkin always casts his movies superbly. There’s great support from Dean Stockwell as a cigar-chomping lawyer who represents Masters, but also ends up giving advice to Vukovich when things start getting really sticky. Debra Feuer as Masters bisexual lover Bianca, Darlanne Fluegel as Chance’s ill-treated girlfriend, John Turturro as Carl Cody, another of Chance’s thorns, and Michael Greene as Chance’s doomed first partner Jimmy Hart who falls prey to Master’s henchmen, “Buddy, you were in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

There is a fantastic, yet utterly shocking twist which occurs in the movie’s last quarter. The movie's denouement caused the producers to panic and they demanded Friedkin shoot an alternate ending. Friedkin complied, but threw it out before the picture was locked off; he was never going to accept such a cop-out. Friedkin explained that the nature of the movie and the way the characters are behaving it was obvious the original ending was very likely to occur, and it is one of the many reasons why To Live and Die in L.A. resonates so potently. It takes no prisoners.