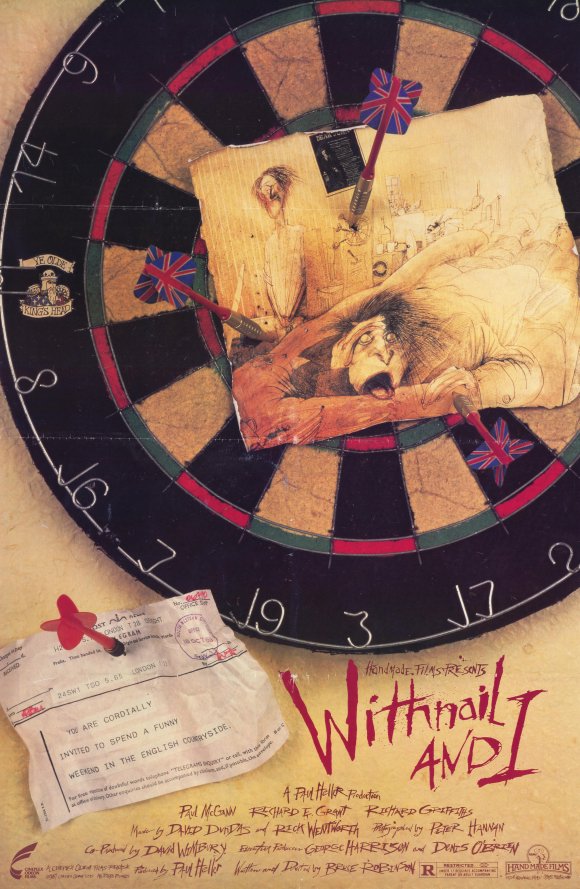

UK | 1986 | Directed by Bruce Robinson

Logline: It’s 1969 and two disheveled, unemployed London actors decide to spend a rejuvenating weekend in the country only to have their escapade turn into a series of embarrassing incidents and disasters.

"We want the finest wines available to humanity. And we want them here, and we want them now!"

Quite frankly I think Bruce Robinson’s semi-autobiographical yarn is one of a rare handful of perfect screenplays. It’s also one of the most moving and affecting films about friendship. And it also happens to be exquisitely funny. I’ve watched this movie more times than any other, except maybe Blade Runner, Apocalypse Now, and Alien.

Story goes that Robinson has circulating a manuscript for a novel he’d written, based on his experiences with a fellow thespian and raving alcoholic named Vivian (whom the character of Withnail is based on). The script ended up in the hands of George Harrison who decided it was suitable for his Handmade Films production company. Robinson was then offered the director’s role. He’d never directed anything before.

During principal photography producers who were viewing some of the rushes complained that there weren’t any gags, and that the movie wasn’t going to be funny enough. They wanted Robinson off the picture. Bruce became enraged, insisting that the comedic effect was cumulative, and based on character, not one-liners (although the movie is endlessly quotable). He was kept on, only after demanding that the producers were not allowed on set under pain of death.

The casting is sensational. Paul McGann is terrific as Marwood (never actually named in the movie and credited only as “… and I”), the more earnest and prospective of the pair, whilst Richard E. Grant’s portrayal of Withnail is a calibrated stroke of genius. As crazy as it seems Grant was a teetotaler, yet delivers arguably the finest depiction of a desperate drunk ever put to celluloid. Then there’s Michael Elphick’s wily poacher Jake (“I’ve been watching you, prancing like a tit, you need working on lad!”), Ralph Brown’s irrepressible drug fiend Danny (“If I spike you, you’ll know you’ve been spoken to!”), and last, but not least, Richard Griffith’s blisteringly camp Uncle Monty (“There is, you’ll agree, a certain je ne sais quoi oh, so very special about a firm, young carrot!”).

Apparently Daniel Day-Lewis was offered the role of Withnail, but declined (he’s great, but no). Kenneth Branagh was tested (eeek!), as was a young Bill Nighy (interesting). In the end, there’s no one else who could’ve pulled off what Grant did with the role. And McGann was the perfect foil.

I could describe the elements in Withnail and I like a beautiful marriage. Every scene compliments the last, every line of dialogue is pitch-perfect, every nuance of character shimmers, and every moment is to be savoured like a 1953 Margeaux or thrown back like a pair of quadruple whiskies and a pair of pints. The original score by David Dundas and Rick Wentworth is magical, and there’s the now infamously inspired use of two Jimi Hendrix tracks; All Along the Watchtower and Voodoo Chile (Slight Return), which prompted the Hendrix family estate to change their licensing policy because they were dismayed over the continued association with drug culture.

Superbly filmed (the location shooting in the Lakeside District is highly memorable, especially in the scene where Marwood in his magnificent leather trench coat steps out of Crow Cragg cottage into the frosty early morning air and has a look around), and deeply poignant, Withnail and I lingers like vintage wine and fond memories. Poor Bruce Robinson has never made any money from the movie, and to rub salt in his wounds, it has one of the strongest cult followings of any English comedy, challenging even Monty Python.

I could write a bloody thesis on this movie – maybe one day I will – but for the meantime I’ll simply bookend my review with another reference to the movie’s key themes of fraternity and loneliness, streaked with irony, where Withnail turns to a few bedraggled, disinterested zoo wolves and recites Act II from Hamlet; “I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth …”

NB: Feel free to try the associated drinking game. You drink whatever and whenever they do.