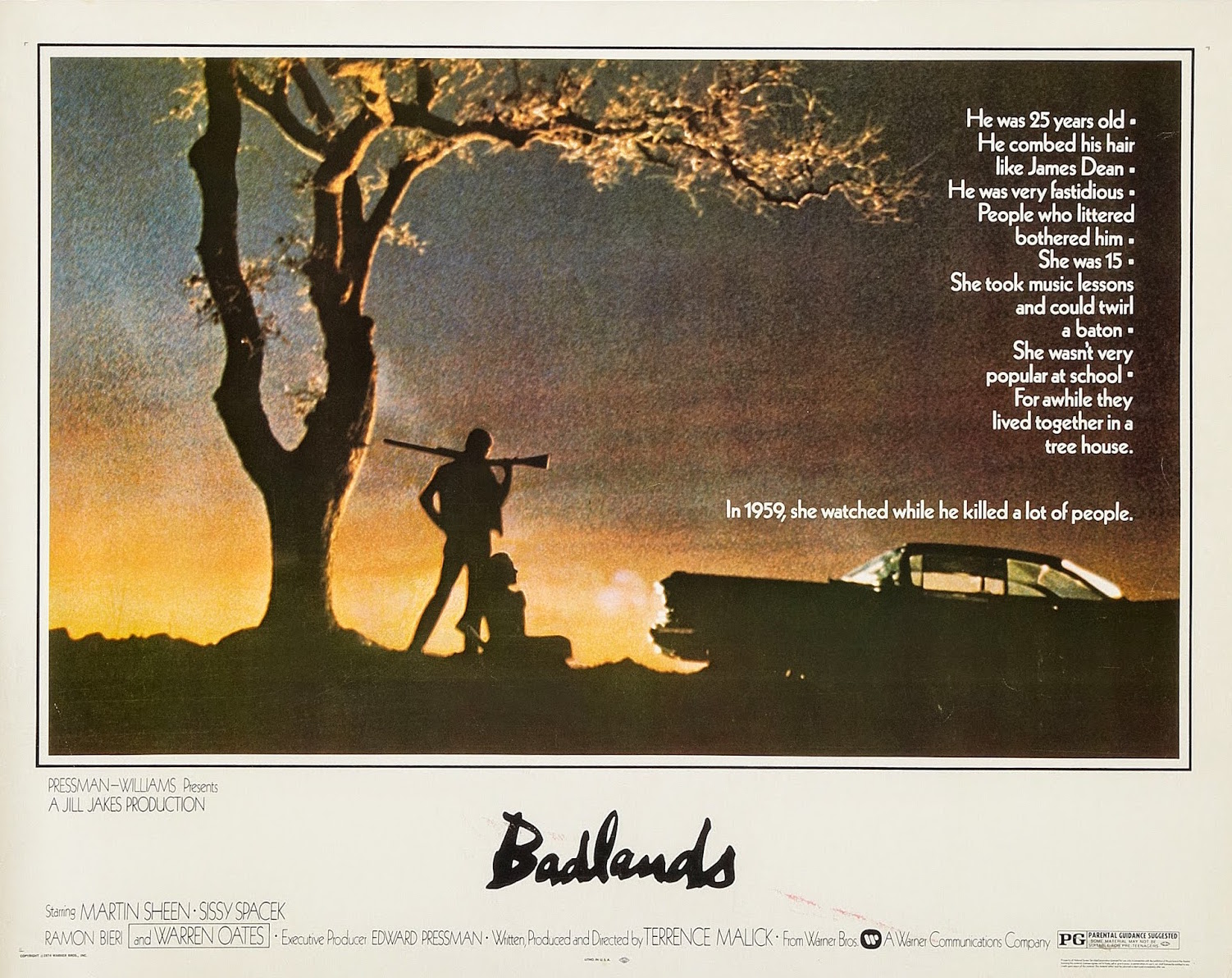

US | 1973 | Directed Terrence Malick

Logline: In the late 50s an impressionable teenage girl is befriended by a reckless young man who leads her into an interstate murder spree.

“Of course I had to keep all of this a secret from my Dad. He would had a fit because Kit was ten years older than me and came from the wrong side of the tracks so called.”

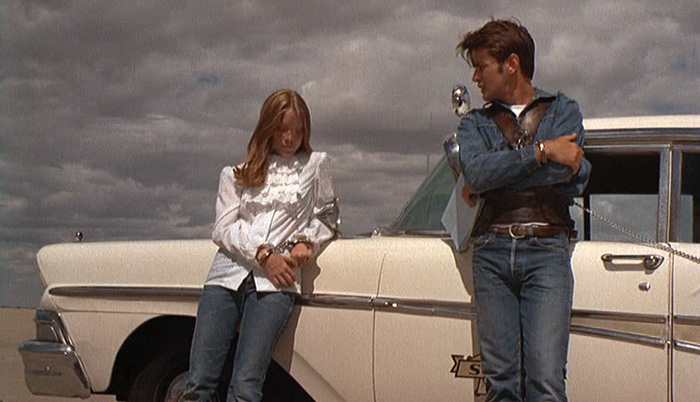

Holly (Sissy Spacek) is a fifteen-year-old girl with her head in the clouds. Her father (Warren Oates), a sign painter, has relocated them into Fort Dupree, South Dakota, and it is here where she meets the handsome, restless Kit (Martin Sheen), a greaser biding his time, toying with escaping the clutches of small town existence. He lures the pretty redhead away from her front yard and before you can say “Good golly, well I'll be damned!” they’ve fallen into a hapless, hopeless infatuation, much to the concern of her strict father.

“Little did I realise that what began in the alleys and back ways of this quiet town would end in the Badlands of Montana.”

It is Holly’s voice-over narration that provides Badlands with its dreamy, juxtaposed morality. It’s as if Holly is watching herself drift along on a picturesque travelogue, unable to intervene, her life inexorably becoming a train wreck in beautiful slow motion. It is love’s sweet adventure that unfurls and traps her in its web and it is life’s bitter irony that leaves her amidst love’s ruin.

Terrence Malick’s feature debut is, arguably, his most accomplished and resonant movie. Loosely based on the real-life killing spree of Charlie Starkweather and his girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate in 1958, although not credited or acknowledged at the time, here’s a conciseness that encapsulates the narrative, that keeps the edges from fraying, yet still manages to harness a poetic sense of the wilderness, of wandering. Malick has always managed to imbue his movies with a soft, dreamy mise-en-scene, even within the framework of a war movie (The Thin Red Line), but with Badlands the narrative and style are so perfectly entwined, it’s hard to imagine anyone else at the helm.

Spacek and Sheen are terrific. Spacek, who was twenty-three at the time captures the wistfulness of a teenager with a delicate charisma and brooding intelligence. Sheen, all James Dean swagger and nonchalance, had already spent fifteen years doing television, with a couple of features under his belt. His performance is amongst the best of his career.

“One day, while taking a look at some vistas in Dad's stereopticon, it hit me that I was just this little girl, born in Texas, whose father was a sign painter, who only had just so many years to live. It sent a chill down my spine and I thought where would I be this very moment, if Kit had never met me? Or killed anybody... For days afterwards I lived in dread. Sometimes I wished I could fall asleep and be taken off to some magical land, and this never happened.”

Three cinematographers worked on the movie, but kudos to Malick for reigning in the visual style with such fluidity, something he’s achieved and maintained on all his movies. It’s interesting to note that the production designer, Jack Fisk, would go on to marry Spacek and work on David Lynch’s Eraserhead, of which Spacek helped secure financing for. It was her experience on Badlands that made her appreciate the artistry of cinema, and aware that visionary filmmakers needed the support. Sheen still regards Malick’s screenplay for Badlands as the best he’s ever read.

Badlands is melancholy and disquieting, undeniably American, brilliantly evocative, and one of my favourite movies of the 70s.