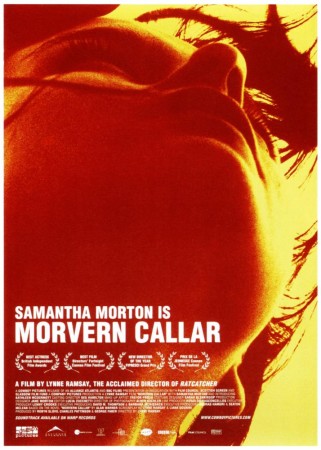

UK/Canada | 2002 | Directed by Lynne Ramsay

Logline: Following her boyfriend’s suicide an impulsive young woman uses his money to go on holiday with her best friend and indulge in a hedonistic lifestyle.

In a career performance Samantha Morton becomes the titular character from Alan Warner’s brilliant 1995 debut novel about a shellshocked and careless woman on a spiralling journey of self-discovery and self-abandonment. The novel is Scottish in origin, however while best friend Lanna (Kathleen McDermott) is full brogue Scots, Morton’s Callar is English. Not that it really matters, Much of the narrative takes place abroad in the tourist hotspots of coastal Spain (the island of Ibiza, mainly).

Many of the novel’s peripheral characters are still floating in and around the narrative (Red Hanna, Cat in the Hat, Dazzer, Couris Jean, Sheila Tequila, Creeping Jesus, and Tom Boddington, the eager beaver literary agent who visits Morvern in Spain), but for almost the entire travelogue, emotionally, psychologically, and physically, the perspective is Callar’s. This is her journey, both inner and outer. But there isn’t an ending, well, not a conventional one, and the movie works all the better for it.

Beautifully shot and edited by Alwin H. Küchler and Lucia Zucchetto, respectively, Morvern Callar has the unusual distinction of having the source material written by a man, but of a woman’s perspective (rare), and the movie adaptation co-penned (with Liana Dognini) and directed by a woman. It is director Ramsay’s female intuition that gives Morvern Callar and added depth of colour and tone. The narrative becomes Ramsay’s vision as viewed through Morvern’s eyes.

There is a sublime, darkened poetry at work within Morvern Callar, watching this fearless, troubled young woman dive into the deep end and swim with the sharks, pretending they’re dolphins. This may very well be Morton’s vehicle, but it is Ramsay navigating and driving. Warner’s novel becomes a shell, but it’s a hard shell with strong, distinct markings.

Ultimately Ramsay isn’t interested in capturing or portraying realism, but neither was Warner. This is a story of inner turmoil, executed through outer impulsions. It is xenophobia embraced, it is gregariousness thrown in a corner, the extroverted held captive. Where is love? It is lying in the warm surf. Where is lust? It’s sprawled on the dancefloor. Where is responsibility? It’s floating in the Champagne. Where is the future? It’s present in the past.

Morvern Callar is an acquired taste, like a ocean delicacy; salty, slippery, viscous, invigorating, elusive, immersive. Samantha Morton and Lynne Ramsay become symbiotic, as they traverse the landscape of the feminine wastrel, the fox unaware of its slyness, the damaged, self-medicated soul who has stitched herself up.

“Where are we going? asks Lanna , after Morvern has made a most ambitious decision involving her dead lover’s manuscript. He’s history, it’s time to find hers. “Somewhere beautiful,” Morvern replies with a grin. Leave your sensibilities behind, let yourself be entranced on this languid, wayward rave.

It’s curious to note that Ramsay didn’t direct again for nearly a decade, finally following up Morvern Callar with the excellent, deeply disquieting We Need to Talk About Kevin.