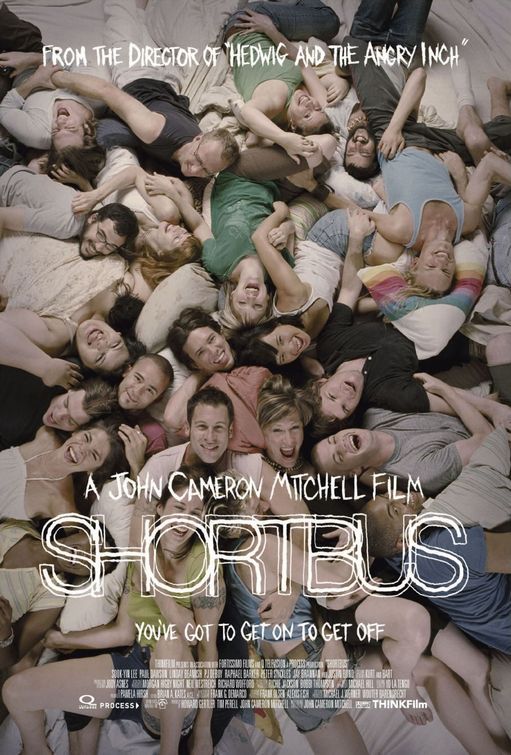

USA | 2006 | Directed by John Cameron Mitchell

Logline: Several gay and straight characters struggle for sexual inspiration and a deeper understanding of love and commitment within their respective relationships.

The title takes its inspiration, perhaps a little obscurely, from the shorter yellow American school bus that often follows the longer traditional one. On board the main bus sit the “normal” kids, while segregated and trailing behind in the short bus are the outsiders; the emotionally-disturbed, dysfunctional misfits. In the movie Shortbus is the name given to an underground salon, infamous for its blend of art, music, politics, and carnality, where the main characters, immersed in their lurid subterfuge, all converge.

The whole look and feel of the film is very NYC; the Big Apple stretching as Grace Jones once crooned. From the brilliant animation sequences that inter-cut the stories – camera flying over a painterly model Manhattan, diving down through the trees of Central Park and zooming into the window of some lower eastside apartment block – to the biting, self-depreciating sense of humour, the nonchalant polysexual tone, and of course, the mischievous, no-holds-barred explicit sex.

Shortbus embraces sexuality with a bear hug and a reach around, part of the mid-noughties' boundary-pushing splurge that included Michael Winterbottom’s tenuous 9 Songs and Catherine Breillet’s contemptuous Romance and Anatomy of Hell. These were movies that featured unsimulated sex (or "actual sex", as the Australian Classification Board prefer to label it). Certainly not the first time in "mainstream" cinema (see 1975's In the Realm of the Senses for one of the early pioneers), but probably with a wider cinema audience than ever before.

Shortbus is one of the first to combine all orientations under one roof. In between the soul-searching and body-issues all proclivities get serviced, including a scene of rather impressive auto-fellatio!

The successful hardcore porn directors of the 70s had pipe dreams that the adult movie industry and Hollywood would eventually merge, but thirty years down the track and the contemporary provocative left-field Tinseltown directors can continue to dream away, as Hollywood will never make a film like this. Thankfully we have a clutch of independent filmmakers who are willing to push the envelope.

Shortbus is the kind of transgressive, genre-bending “mainstream” filmmaking that only rears its head periodically. Many stick-in-the-mud viewers will see it as nothing more than elevated porn, but hey, sex and art have always tangoed. Mitchell elicits performances that are surprisingly solid, injecting the film with intelligence, honesty, and a genuinely emotional edge. While the narrative meanders from time to time, its central themes of self-acceptance and open-mindedness anchor the movie.

Vividly colourful and frequently funny, it's an outrageous melting pot of underground styles ejaculating over the mainstreet. Think Federico Fellini meets John Cassavetes meets Nicole Holofcener meets Richard Linklater meets Robert Altman meets Jack Smith meets Woody Allen at a swingers club in downtown New York City, and you’ll get Mitchell's acquired taste. Whether you spit or swallow is up to you.