US | 1987 | Directed by Prince

Logline: A concert film based around Prince’s titular album.

Concert films are a dime a dozen, but few capture the pure essence of the artist as richly, atmospherically, or as passionately as the movie that followed the release of Prince's ninth studio album, 1987’s Sign o’ the Times. The movie that focused on the stage show based on his European tour was as singular and powerful as Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains the Same, Talking Heads’ Stop Makin’ Sense, or Neil Young’s Year of the Horse. It has become a cult phenomenon as colourful and dynamic as Woodstock or Monterey Pop, and as memorable and emotionally affecting as The Rolling Stones’ Gimme Shelter or U2's Under a Blood Red Sky. It is Prince captured at the zenith of his creative, flamboyant influence, with an extraordinary band to boot.

Prince’s following in Europe had been building steadily since 1980’s Dirty Mind, the album that heralded the arrival of the Prince most of us recognize, the agent provocateur with more funk in his bounce than the average street cat. Prince toured extensively across Europe with his Sign o’ the Times Tour where sales were very strong, yet on his home turf the sales weren’t as impressive, and a concert film, to be distributed extensively in America, was devised to help bolster sales in the US. Live footage from concerts in the Netherlands and Beligum were intended to be used, but Prince was not happy with the results, and as such, around 80% of the concert film was re-staged and shot at Paisley Park, including an intro and series of vignettes that link the songs with a loose narrative about love, sex, and religion (the usual Prince fuel).

Although the director credit is given to Prince, Albert Magnoli, who directed Purple Rain, did a substantial amount of uncredited work. Considering Prince’s previous directorial effort, Under the Cherry Moon, was so lambasted, it’s surprising that Prince would insist on helming the live project, but as the results show, Prince on stage as a showman outshines his hammy performance as a playboy on the Riveria. Indeed, Prince delivers a career performance in Sign o’ the Times.

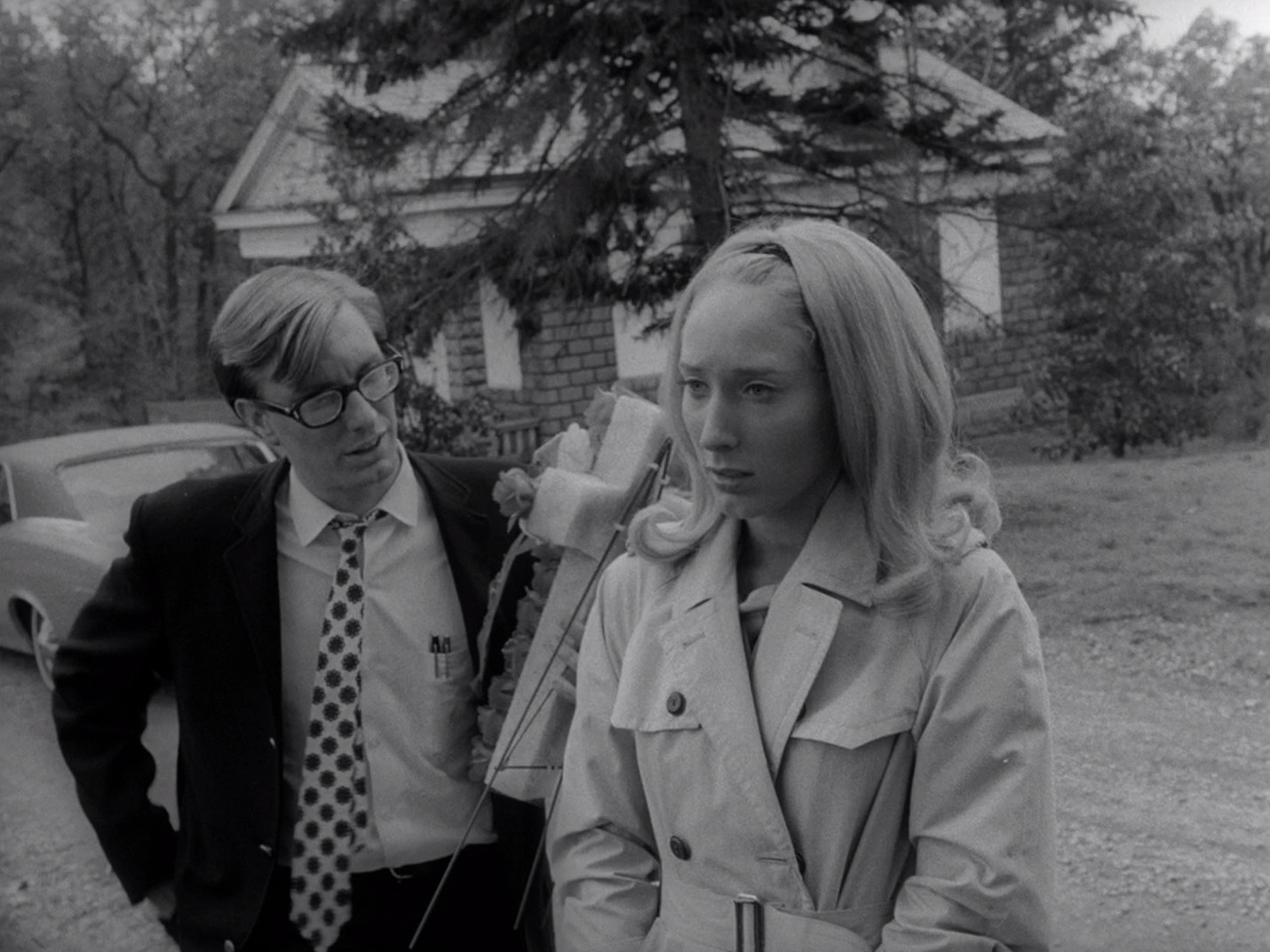

The prologue is a street hustle and bustle between Cat, Prince’s dancer and back-up singer, and Wally Safford, one of Prince’s sidekicks. Prince grabs Cat by the hand and steals her away, to a crystal ball, firing purple bolts of electricity, and they gaze into the sphere.

Alone on a stage designed to look like a cross between the dirty neon of old 42nd Street and the streetwise grime of Harlem or The Bronx, the concert opens with the album’s title track in which The Purple One laments the state of the world. Suddenly marching band drumming cuts through the song in syncopation and the rest of the band enter stage right, single file, each one armed with a snare; Cat, Wally, Greg Brooks (backup vocals), Boni Boyer (keys), Miko Weaver (guitar), Levi Seacer Jr. (bass), Dr. Fink (synths), Atlanta Bliss (trumpet), Eric Leeds (sax), and Sheila E. (drums). They end in unison, and the crowd erupts. This is a pure celebration of Prince 's musical genius, unfettered, indulgent, uplifting, mesmerising.

Indeed, prepare to be wowed, as the band kick proverbial ass through a roughly 80-minute set of searing funk jams and power ballads from the titular album, plus a dash of Charlie Parker ("Now’s the Time") thrown in for good jazzy measure, and not forgetting a blistering, awe-inspiring drum solo courtesy of percussionist extraordinaire Sheila E (even Prince gets behind the kit at one point!) The only other non-album song played is a tease of "Little Red Corvette" early on.

If I had one gripe, it’s that the inclusion of the promotional video for the single "U Got the Look" looks and feels out of place. It was filmed well in advance of the concert footage, and as such features a different stage design, the performers have altered haircuts, and there's the grainy, harsh quality of the video itself. Time has not been kind to that creative decision, whether it was Prince’s or his management, and it would’ve been judicious to have released a 30th anniversary HD edition with that four minute insert removed, and instead, provided as a separate extra.

But irk aside, because it’s a small one really, Sign o’ the Times is a truly magnificent experience. It’s hard to pick favourites. Each time I watch the movie I change my mind. Sometimes it’s the epic "I Could Never Take the Place of Your Man", with that soaring, heart-wrenching guitar solo, cleverly segueing into a coda that incorporates the brass section lifted from “Rockhard in a Funky Place”. On other viewings it’s the goosebumpin’ organ intro to “Hot Thing”, or the breezy gouster strut of “If I Was Your Girlfriend”, or maybe the marathon soul chant of “Forever in My Life”.

Or perhaps it’s the stripped back rock pledge of “The Cross” that brings the movie to an end. Any which way, it’s loose and brilliant, and there will never be another maestro like His Royal Badness, so thank the heavens we have Sign o’ the Times to help ease our minds, hearts, and souls.

Watch it for the first time, watch it for the umpteenth. Just watch it, because it's always gonna be a beautiful night. Always, every time.