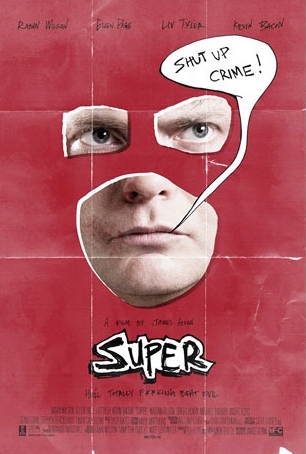

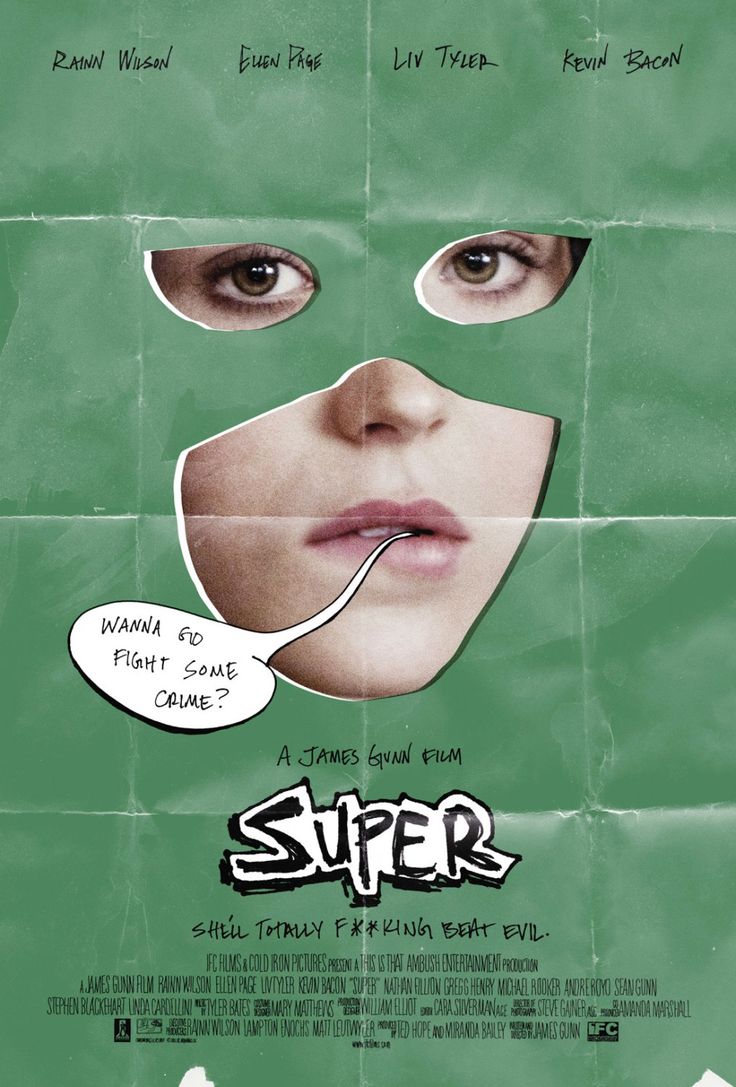

US | 2010 | Directed by James Gunn

Logline: After his wife falls under the influence of a drug dealer an ordinary guy becomes a superhero, but is severely lacking in heroic skills.

Dorky Frank (Rainn Wilson) loves beautiful Sarah (Liv Tyler) and they wed in a blissful bubble soon to be burst. Sarah likes the bong and it seems she likes more what “interesting” Frank can offer.

WHAM!

Jacques (Kevin Bacon) steals Sarah away, seducing her with harder drugs and longer nights. Frank falls into misery and despair and in desperation he turns to God to show him the light that will back his true love. God touches Frank and presents a vision of superness.

BAM!

Frank takes heed from The Holy Avenger (Nathan Fillion) and transforms into Crimson Bolt! Saying “Shut up, crime!” and armed with a trusty wrench, Crimson Bolt dishes out extreme prejudice – justice – to those evil crime doers: the drug dealers, the child molesters, those who profit off the misery of others, those that butt into queues!

THANK YOU, MA’AM!

Super is a fantastic slap in the face for comic book fans, freakazoids, and those who like their comedy laced with toxic darkness. Gunn takes the satire bull by the horns and bites the morality bullet, then spits it back out, and says “Fuck you!” … If you follow your heart, the surface shit melts away leaving the truth exposed like a bleeding organ. Take that organ and squeeze it ‘til it hurts. Life is full of emotional pain and bitter irony, a journey where Murphy’s Law can pound you into the ground. But the “super” inside you can prevail!

Gunn worked for the Troma camp cutting his perversive, subversive teeth and getting his hands grimy and calloused on Tromeo and Juliet. He wrote the excellent screenplay to Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead (2004) re-boot, he wrote and directed the hilarious science-fiction-horror spoof Slither (2006), and most recently delivered, arguably, the most entertaining Marvel movie yet, Guardians of the Galaxy.

The movie’s relatively low budget (considering the cast) doesn’t hinder the movie’s intent, as Gunn delivers cleverly and economically. He elicits sensational performances from his two leads, with Ellen Page causing unexpected ripples of cosplay lust through the audience when she dons that slinky eye-mask as Frank’s sidekick, Boltie! Gunn winks at his fans by casting Michael Rooker as one of Jacques’s thugs, as Rooker was the lead in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986), the movie that apparently had the biggest impact on Gunn’s in his formative years.

Putting it bluntly, but succinctly, Super kicks Kickass’s arse! The movie’s amorality, its sly, and oh so wicked sense of humour, the graphic ultra-violence that shocks as much as it triggers satisfaction; all of it is a superb manipulation of convention and expectation. Oh, and a bang-on soundtrack to boot! Pop some corn, rip the scabs off some tinnies, roll some blunts, whatever, just leave your sensibilities at the door and get in amongst it, this is an anarchic hoot of the highest order.