New Zealand | 1981 | Directed by Roger Donaldson

Logline: A former Grand Prix driver and obsessive auto mechanic resorts to desperate measures in order to maintain custody of his young daughter after his wife walks out on him and takes his close friend as her lover.

Roger Donaldson would go on to direct the excellent Hollywood political thriller No Way Out, but his second movie is my favourite New Zealand feature. There’s a spare momentum that drives the narrative, and a deep sense of melancholy that permeates the characters. It also happens to be filmed in a region very close to my heart; near Mt. Ruapehu in the volcanic plateau of the North Island.

The "Smash Palace" of the title refers to a massive, sprawling auto cemetery (in reality the legendary Horopito Motors); a junkyard owned by Al Shaw (Bruno Lawrence) who lives there with his French wife Jacqui (Anna Jemison) and their 8-year-old daughter Georgie (Greer Robson). A mate Tiny (Desmond Kelly) helps out in the main garage, while local police officer Ray (Keith Aberdein) is Al’s drinking and snooker pal.

Jacqui, however, is not a happy woman. Al doesn’t pay her enough attention, too absorbed in his vehicular tinkering. He’s got an important upcoming race and he wants his beautiful machine in perfect condition. So Jacqui finds interest elsewhere; Ray, to be precise. Al takes things badly.

With a stunning score by then-popular Kiwi songstress Sharon O’Neill and beautiful cinematography from Greame Cowley - the opening scene is brilliant; (the gaffer, Stuart Dryburgh, would go on to become the best cinematographer New Zealand’s ever seen), Smash Palace captures a lingering sense of rural loneliness that becomes a subtle metaphor for the breakdown of Al and Jacqui’s marriage and the alienation that threatens Al’s sanity.

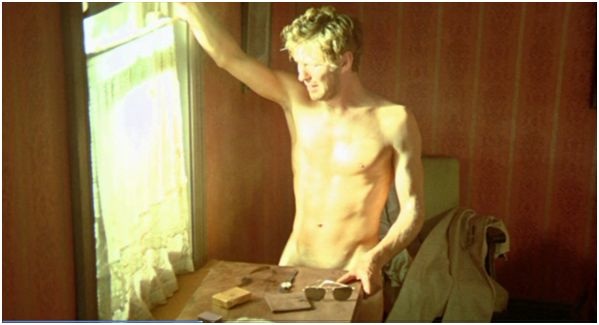

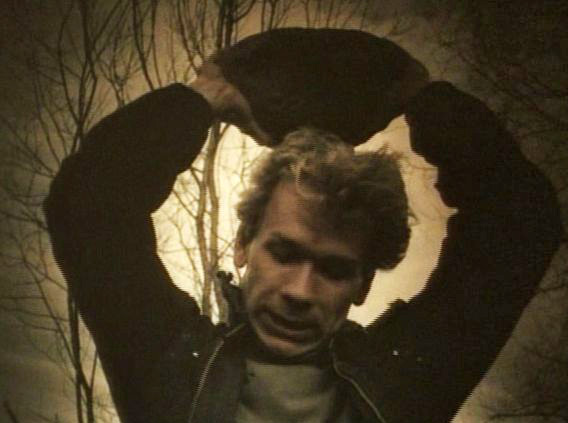

The screenplay, co-written between Donaldson, Peter Hansard and Bruno Lawrence is tight and effective balancing scenes of emotional fragility, lighthearted frivolity, and when the moment serves, intense drama. There’s also a surprisingly erotic sex scene, and in the movie's most disarming scene, an equally frank moment of full-frontal nudity from Lawrence (Bruno was never shy about getting his gear off for the sake of a good story).

Apart from the powerful thematic elements to the movie, it is the central performances of Jemison and Lawrence that give Smash Palace such resonance. There is chemistry between them, even if it’s already dissipating from movie’s start, and you genuinely feel Al’s frustration and rage, as well as Jacqui’s own frustration and anguish. Caught in the middle are Georgie and Ray. Not to forget young Margaret Umbers amusingly irritating, brief role as a hysterical pharmacy counter girl whom Al takes hostage.

A curious aside: In New Zealand there was a division; the police, and as a separate law enforcement body, the traffic cops. The fuzz were in blue and white cars and the “coffee traps” (as my father used to call them) were in black and white. Eventually they merged as one long arm of the law.